- You are here:

-

Home

-

News

- Latest News

Lots of exciting things are happening at Kielder Observatory, use this page to browse the latest stories. We’ll have updates on the events we run, fantastic images our team have taken up at the observatory and occasionally science updates that our team would like to share!

We also release quarterly newsletters via email, sign up to our mailing list and view our archive of past newsletters here:

What's Up? March 2026

In March, we will officially leave the dark days of winter behind us. The spring (or vernal) equinox falls on 20 March, marking the point in Earth’s orbit where neither hemisphere will be tilted toward or away from the sun. This means we’ll experience an equally long day and night. More daylight is certainly cause for celebration, but so are the multitude of March sky offerings, including new constellations, a lunar eclipse visible to nearly a third of the world’s population, and galaxies galore!

Read Time

5 minutes

In March, we will officially leave the dark days of winter behind us. The spring (or vernal) equinox falls on 20 March, marking the point in Earth’s orbit where neither hemisphere will be tilted toward or away from the sun. This means we’ll experience an equally long day and night. More daylight is certainly cause for celebration, but so are the multitude of March sky offerings, including new constellations, a lunar eclipse visible to nearly a third of the world’s population, and galaxies galore!

[fulltext] =>

What's Up March 2026

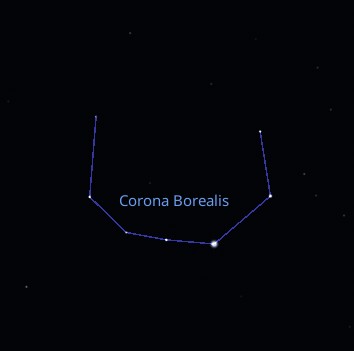

Constellations

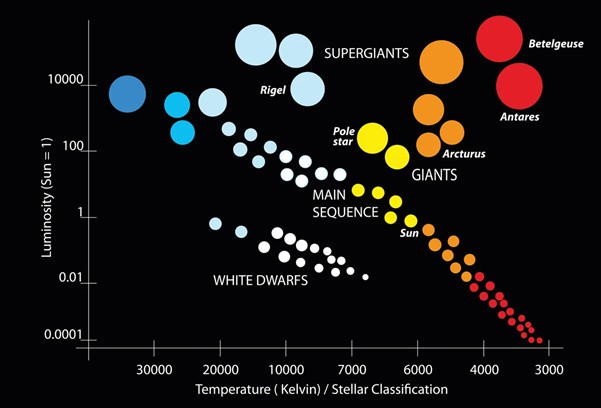

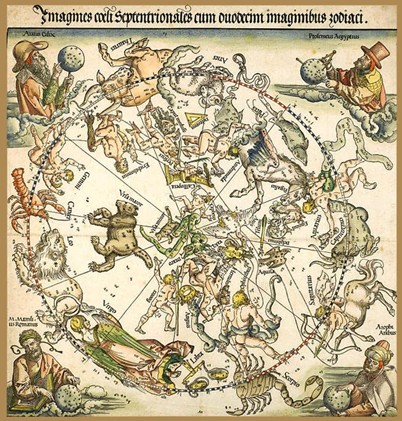

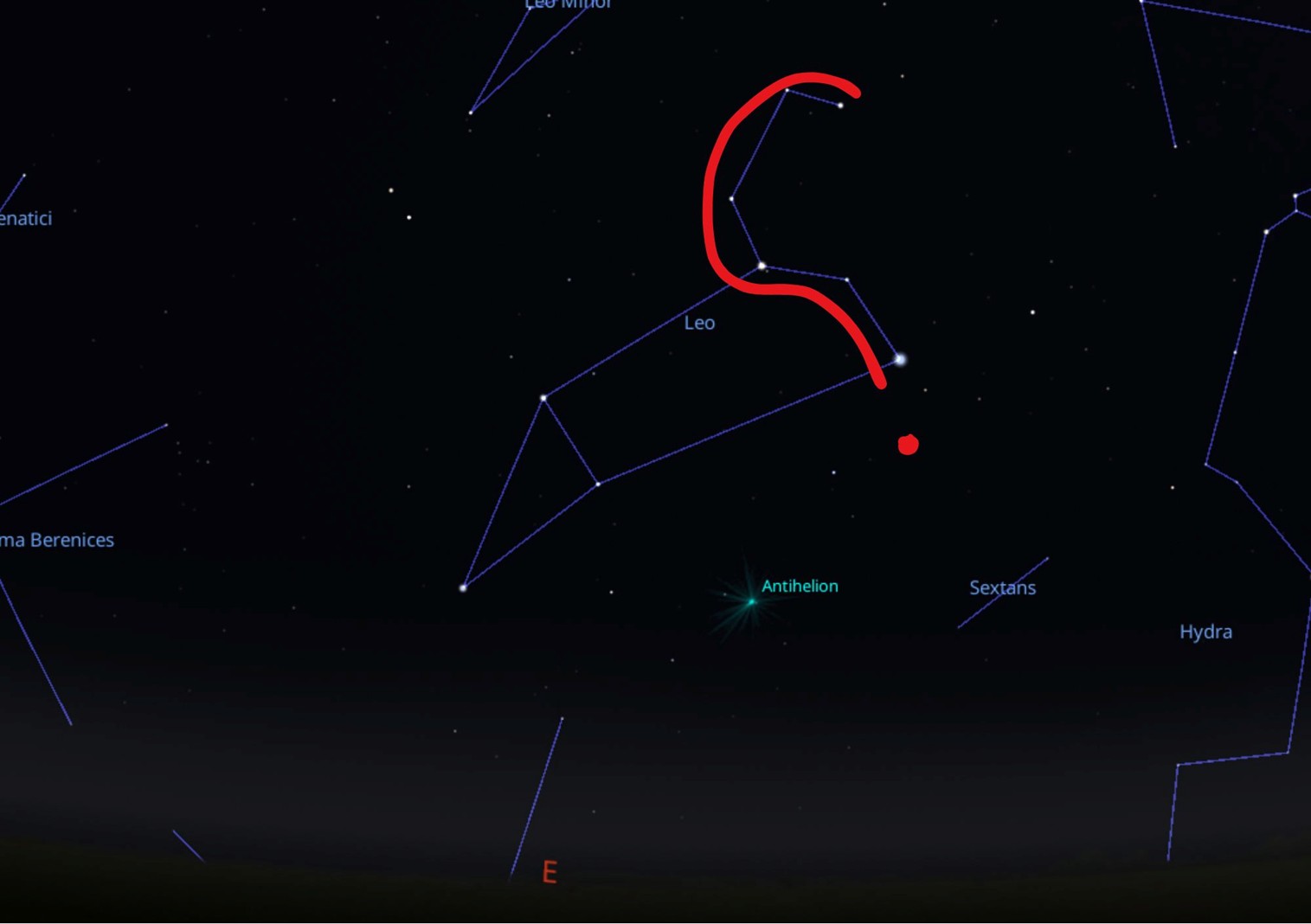

Winter melts into the spring sky and we enjoy the best of both seasons’ offerings. We can still behold the bright stars that comprise the Winter Triangle asterism: Sirius (Canis Major), Procyon (Canis Minor) and Betelgeuse (Orion), and the constellation Boötes is now high enough to appreciate the star Arcturus. At 37 light years away, the red giant Arcturus appears as the second brightest star in the March sky, outshined only by Sirius. To find Arcturus, follow the curve of Ursa major’s tail, Alioth, Mizar, and Alkaid until the next brightest star.

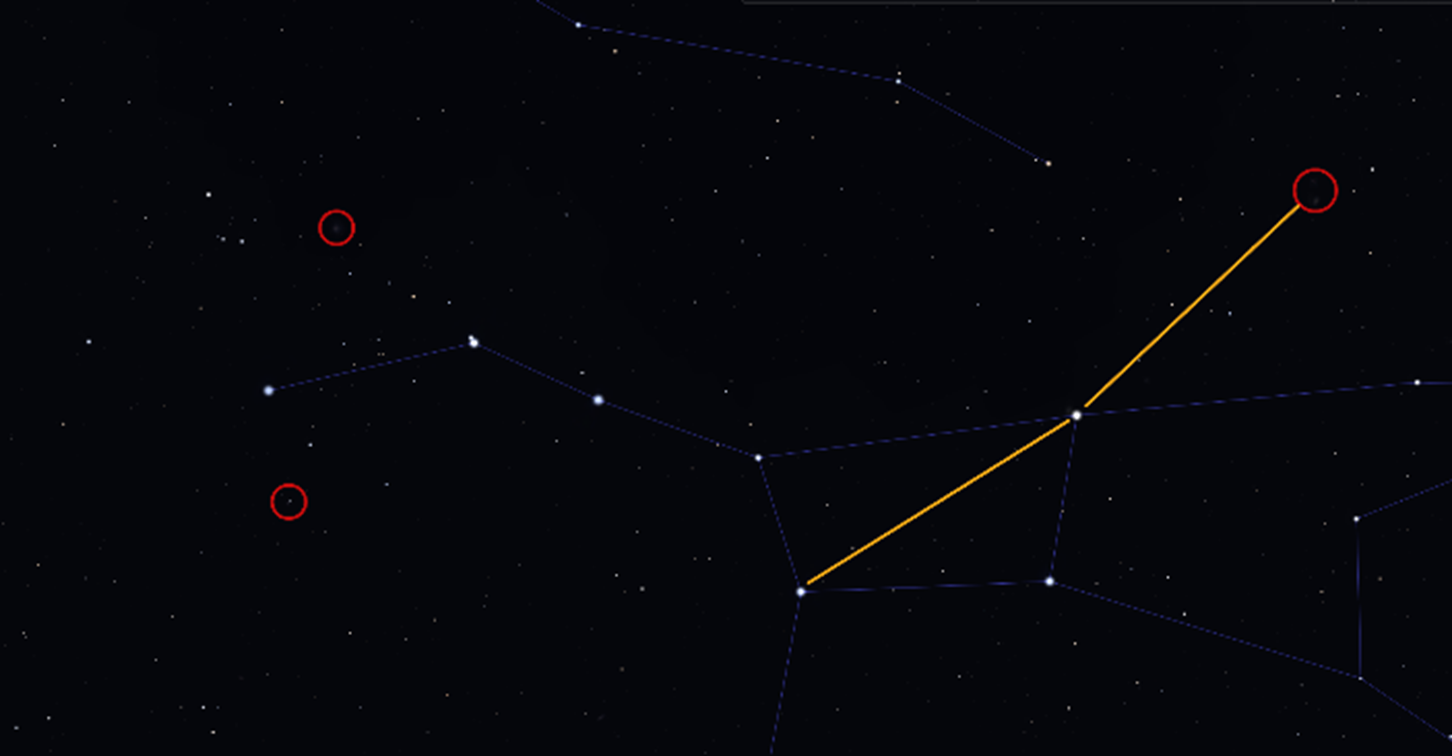

Finding Arcturus from Ursa Major by following the curve of the stars Alioth, Mizar, and Alkaid.

Simulated sky above Kielder Observatory on 15 March at 2200. Credit: Stellarium

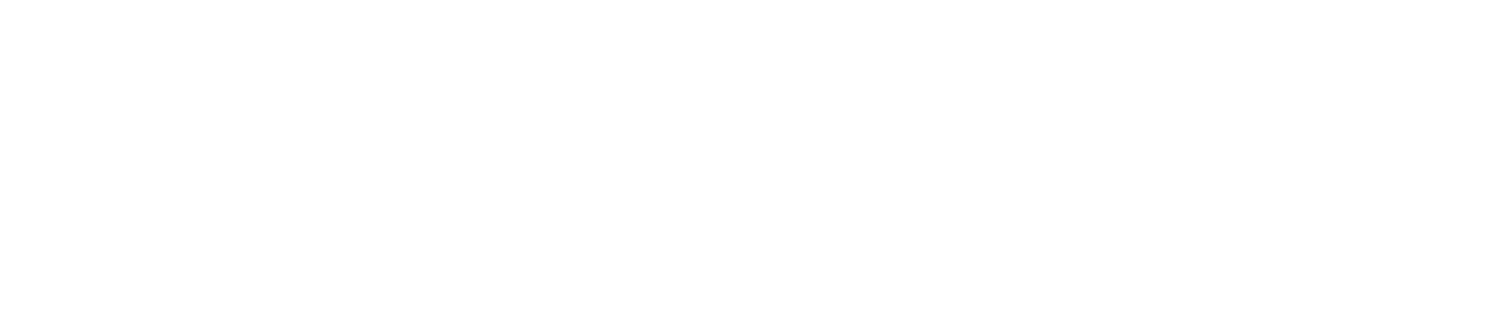

Object of the Month

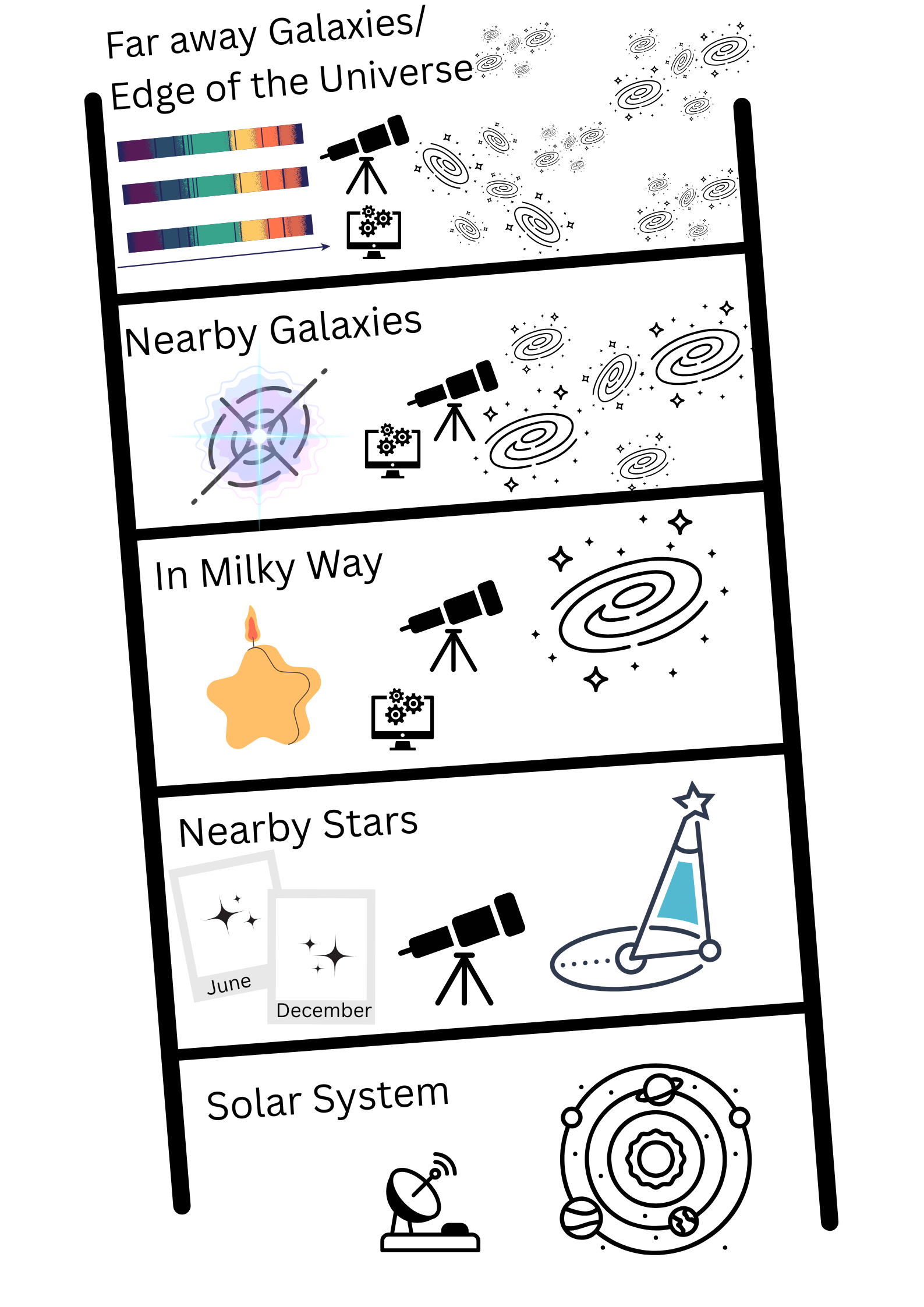

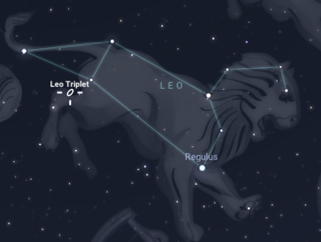

Happy galaxy season! From March to May, astronomers point our telescopes to the emerging constellations Leo, Coma Berenices, and Virgo where we find some of the most rewarding galaxies. Though they often require more powerful telescopes than just binoculars – and still may just appear as smudges – the challenge is all part of the fun!

To usher us into galaxy season, our object of this month is the pinwheel galaxy.

The Pinwheel Galaxy gives us a head-on view of the spiral galaxy. Located 25 million light years away, the galaxy stretches 170,000 light years across (twice the diameter of the Milky Way) and contains about 1 trillion stars. Young, hot stars glow blue in the galaxy’s spiral arms.

Hubble image of the pinwheel galaxy. Credit: NASA, ESA, K. Kuntz (JHU), F. Bresolin (University of Hawaii), J. Trauger (Jet Propulsion Lab), J. Mould (NOAO), Y.-H. Chu (University of Illinois, Urbana) and STScI; CFHT Image: Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope/J.-C. Cuillandre/Coelum; NOAO Image: G. Jacoby, B. Bohannan, M. Hanna/NOAO/AURA/NSF

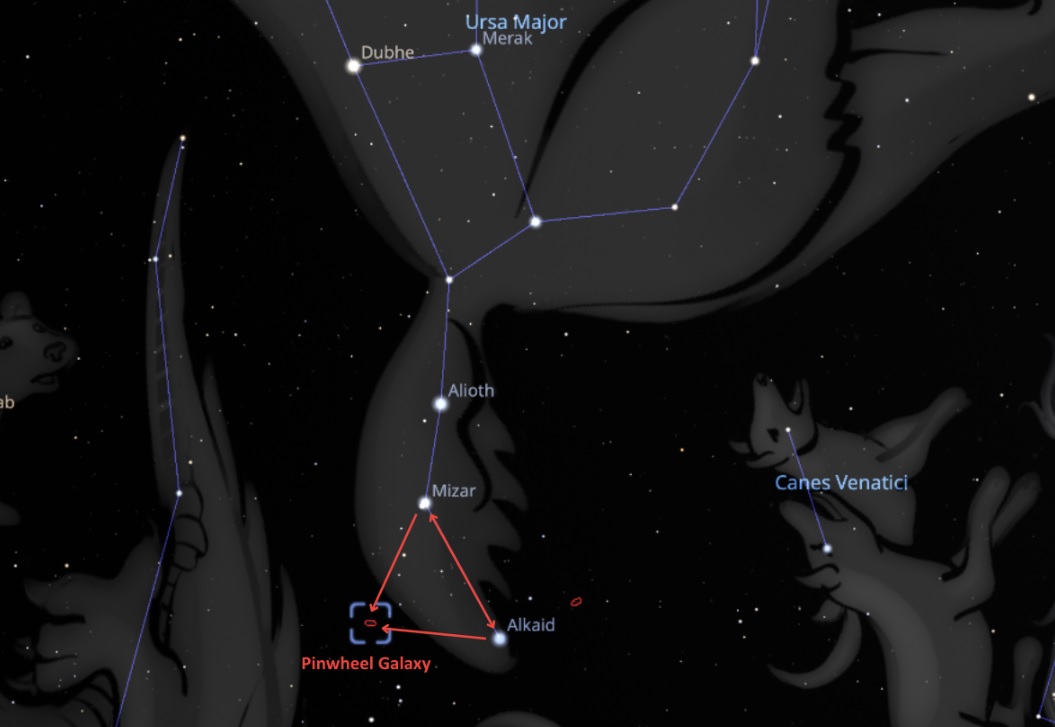

M101 - Pinwheel Galaxy (NGC 5457) possible to spot with 10x50 binoculars in a dark sky. Located in Ursa Major, the Pinwheel Galaxy is highest in the sky though the spring. You can find it by creating an imaginary equilateral triangle above the two last stars in Ursa Major’s tail, Alkaid and Mizar.

Find the Pinwheel Galaxy (M101) by making an equilateral triangle above Ursa Major’s tail using the stars Mizar and Alkaid. Credit: Stellarium.

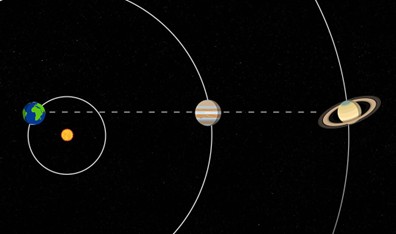

Planets

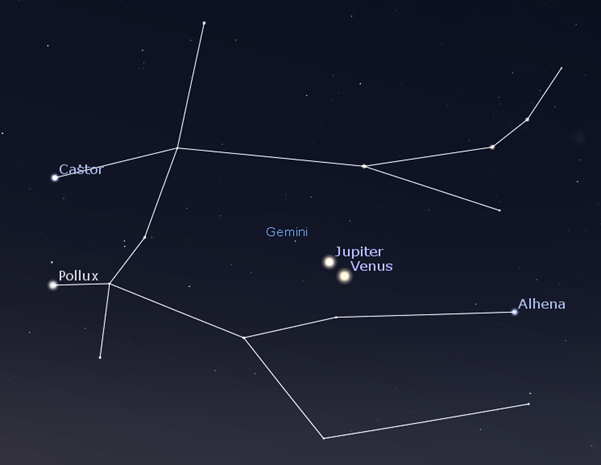

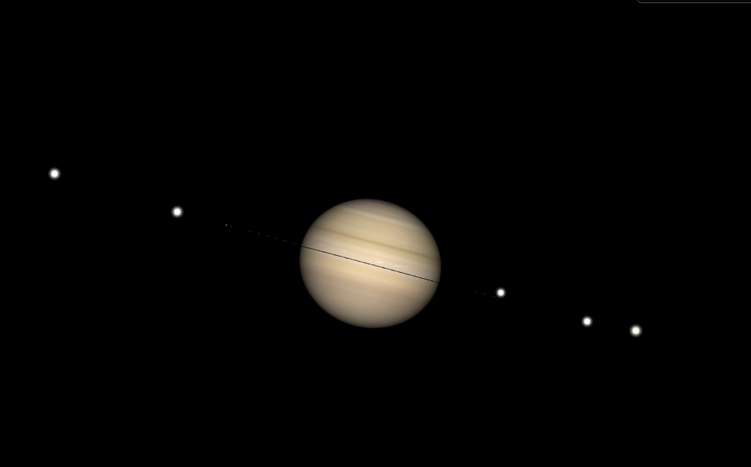

Jupiter still shining in Gemini as the second brightest object in the sky, after to the moon.

Venus visible in the early evening sky just off the western horizon, following closely behind the sun.

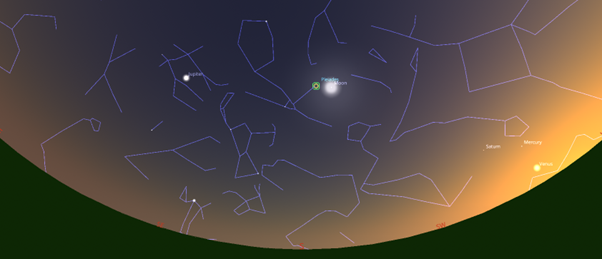

On 8 March, there will be a Venus-Saturn conjunction where the two planets will appear close together in the sky, withing 1 degree of separation or roughly the width of a thumb held at arm’s length. The occurs just around sunset for us in the UK.

Following the conjunction, Saturn will sink below the horizon until 12 April, when it will appear in the morning sky.

The Moon

Full Moon: 3 March

Last Quarter: 10 March

New Moon: 18 March

First Quarter: 25 March

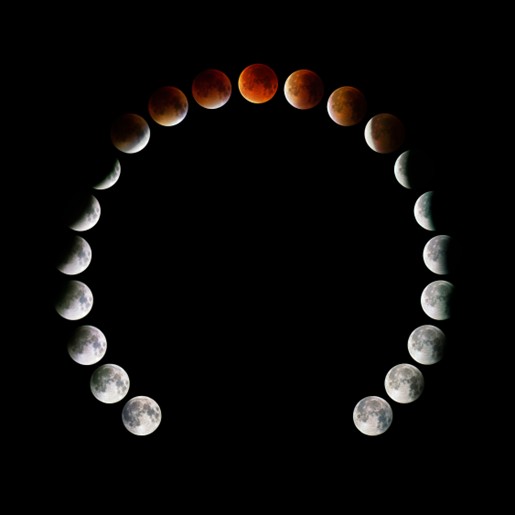

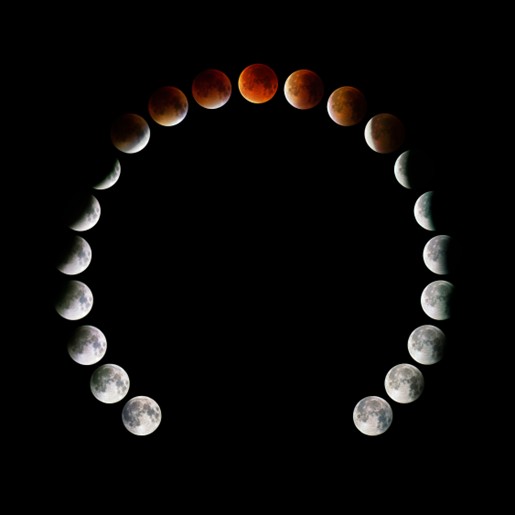

The 3 March full moon, dubbed the worm moon, is also a lunar eclipse visible for North America, Australia, New Zealand, East Asia, and the Pacific. About 31% of the world’s population can enjoy this astronomical event.

The eclipse will take place between 0844-1422 GMT. The moon will ambré into an orange glow during the penumbral phase as it positions behind Earth. At totality, between 1104-1202 GMT (peaking at 1133 GMT) the moon will glow red. After the 58-minute totality, the moon will recede back to its regular colouring.

Image of the 21st January 2019 lunar eclipse taken from Kielder Observatory.

This image is sold as a print in the Kielder Observatory Gift Shop! Credit: Dan Monk

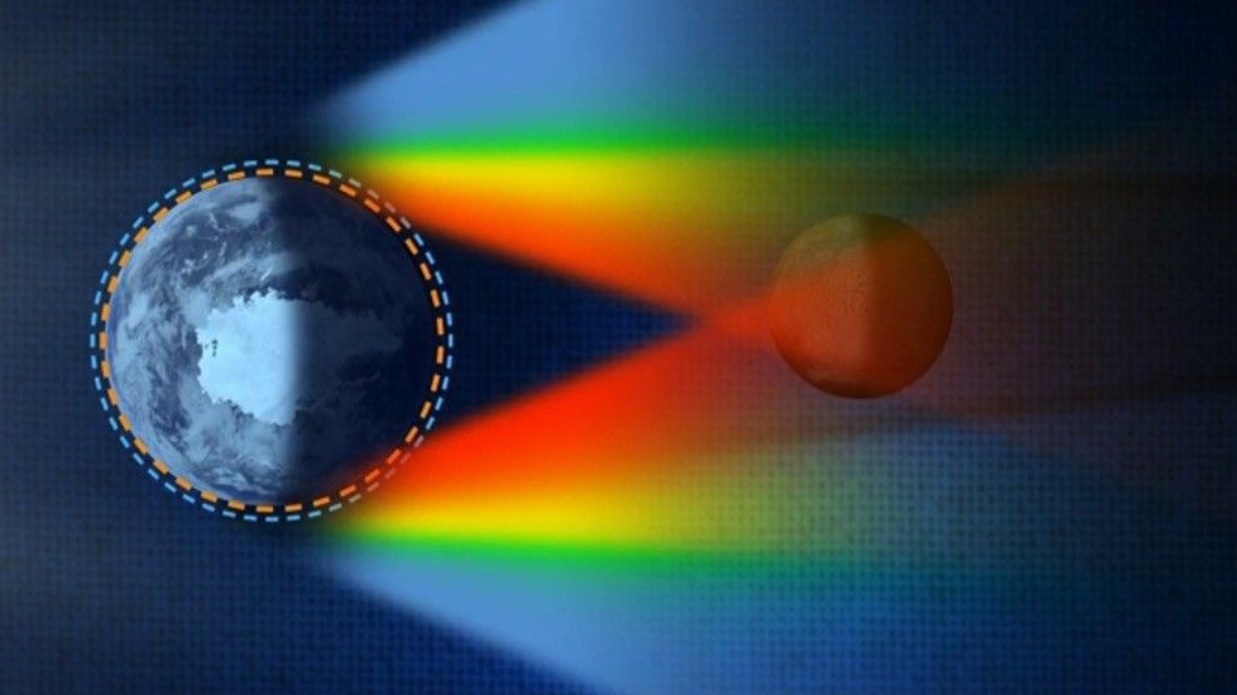

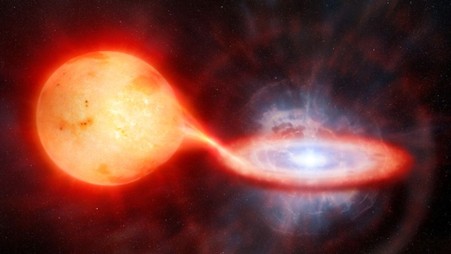

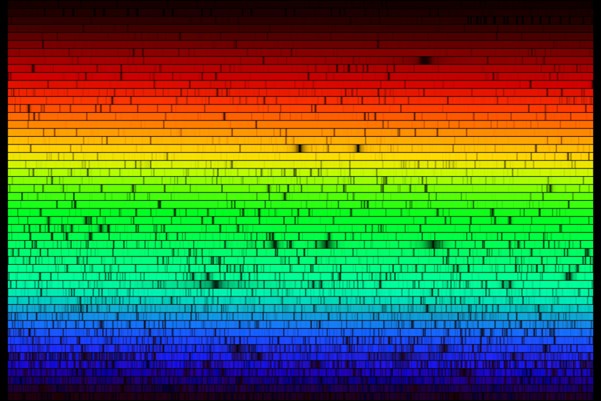

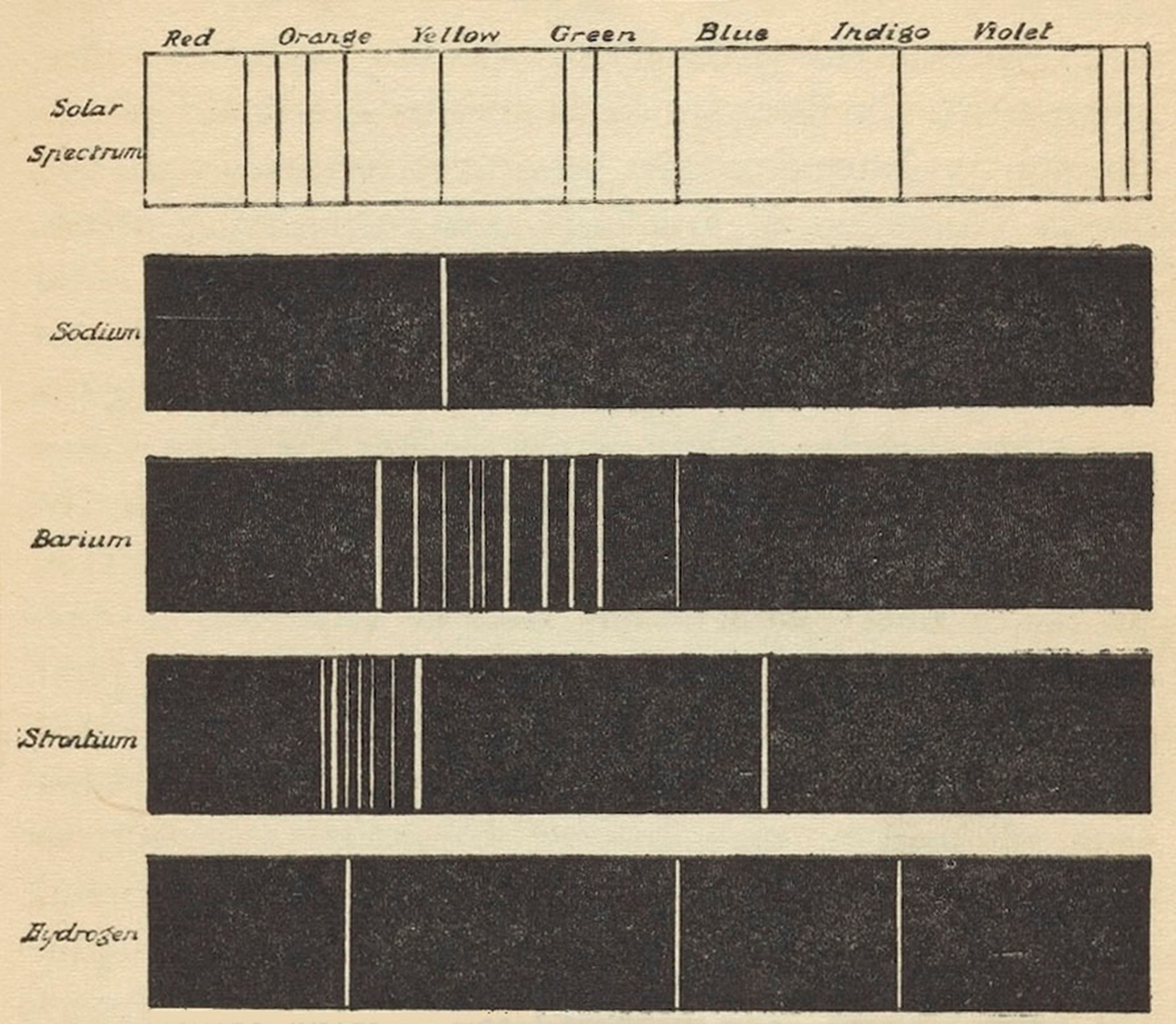

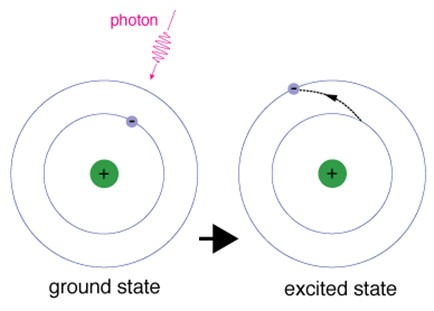

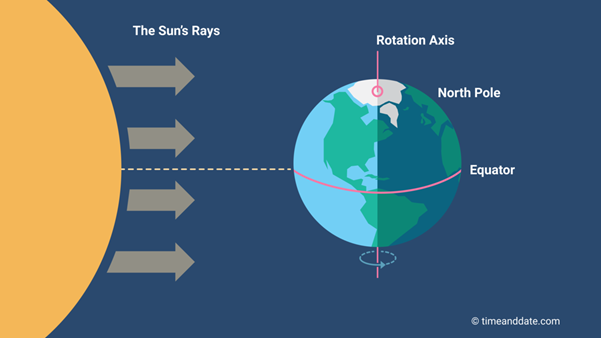

Lunar eclipses occur when the moon aligns directly opposite the sun from Earth. Sunlight, which would otherwise shine directly on the moon’s face, passes through Earth’s atmosphere. Though sunlight appears white, it consists of a spectrum of colours that diffract in the differently in the atmosphere. The shorter blue wavelengths of light scatter away and the longer yellow, orange, and red wavelengths of light pass through the atmosphere to shine on the moon – making the moon appear a rusty orange-red.

Light passing through Earth’s atmosphere casts the moon in a red shadow during a lunar eclipse.

Credit: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center/Scientific Visualization Studio

The lunar eclipse is safe to view with the naked eye, unlike solar eclipses. The eclipse also does not require binoculars or telescopes to appreciate.

[checked_out] => 0 [checked_out_time] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [catid] => 34 [created] => 2026-02-13 17:20:34 [created_by] => 72927 [created_by_alias] => [modified] => 2026-02-25 14:54:59 [modified_by] => 21099 [modified_by_name] => Miss Heather Woodfine [publish_up] => 2026-02-13 17:21:10 [publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [images] => {"image_intro":"images\/whatsup\/Planetary-Parade---Dan-m.jpg","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"Planetary parade in March 2026","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [urls] => {"urla":false,"urlatext":"","targeta":"","urlb":false,"urlbtext":"","targetb":"","urlc":false,"urlctext":"","targetc":""} [attribs] => {"show_title":"0","link_titles":"","show_tags":"","show_intro":"0","info_block_position":"","info_block_show_title":"","show_category":"","link_category":"","show_parent_category":"","link_parent_category":"","show_author":"","link_author":"","show_create_date":"","show_modify_date":"","show_publish_date":"","show_item_navigation":"","show_icons":"","show_print_icon":"","show_email_icon":"","show_vote":"","show_hits":"","show_noauth":"","urls_position":"","alternative_readmore":"","article_layout":"","show_publishing_options":"","show_article_options":"","show_urls_images_backend":"","show_urls_images_frontend":""} [metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"","rights":"","xreference":""} [metakey] => [metadesc] => [access] => 1 [hits] => 248 [xreference] => [featured] => 0 [language] => * [readmore] => 6195 [state] => 1 [category_title] => Latest News [category_route] => uncategorised/latest-news [category_access] => 1 [category_alias] => latest-news [author] => Lindsey Brown [author_email] => lindsey@kielderobservatory.org [parent_title] => ROOT [parent_id] => 1 [parent_route] => [parent_alias] => root [rating] => [rating_count] => [published] => 1 [parents_published] => 1 [alternative_readmore] => [layout] => [params] => Joomla\Registry\Registry Object ( [data:protected] => stdClass Object ( [article_layout] => _:default [show_title] => 1 [link_titles] => 0 [show_intro] => 1 [info_block_position] => 0 [info_block_show_title] => 0 [show_category] => 0 [link_category] => 0 [show_parent_category] => 0 [link_parent_category] => 0 [show_author] => 0 [link_author] => 0 [show_create_date] => 0 [show_modify_date] => 0 [show_publish_date] => 0 [show_item_navigation] => 0 [show_vote] => 0 [show_readmore] => 1 [show_readmore_title] => 0 [readmore_limit] => 100 [show_tags] => 0 [show_icons] => 0 [show_print_icon] => 0 [show_email_icon] => 0 [show_hits] => 0 [show_noauth] => 0 [urls_position] => 0 [show_publishing_options] => 1 [show_article_options] => 1 [save_history] => 1 [history_limit] => 10 [show_urls_images_frontend] => 0 [show_urls_images_backend] => 1 [targeta] => 0 [targetb] => 0 [targetc] => 0 [float_intro] => right [float_fulltext] => none [category_layout] => _:blog [show_category_heading_title_text] => 1 [show_category_title] => 0 [show_description] => 1 [show_description_image] => 0 [maxLevel] => 1 [show_empty_categories] => 0 [show_no_articles] => 1 [show_subcat_desc] => 1 [show_cat_num_articles] => 0 [show_cat_tags] => 1 [show_base_description] => 1 [maxLevelcat] => -1 [show_empty_categories_cat] => 0 [show_subcat_desc_cat] => 1 [show_cat_num_articles_cat] => 1 [num_leading_articles] => 0 [num_intro_articles] => 27 [num_columns] => 1 [num_links] => 4 [multi_column_order] => 0 [show_subcategory_content] => 0 [show_pagination_limit] => 1 [filter_field] => hide [show_headings] => 1 [list_show_date] => 0 [date_format] => [list_show_hits] => 1 [list_show_author] => 1 [orderby_pri] => order [orderby_sec] => rdate [order_date] => published [show_pagination] => 1 [show_pagination_results] => 1 [show_featured] => show [show_feed_link] => 1 [feed_summary] => 0 [feed_show_readmore] => 0 [show_page_heading] => 0 [layout_type] => blog [menu_text] => 1 [menu_show] => 0 [secure] => 0 [page_title] => Latest News [page_description] => Kielder Observatory Astronomical Society [page_rights] => [robots] => [access-view] => 1 ) [separator] => . ) [displayDate] => 2026-02-13 17:20:34 [slug] => 488:what-s-up-march-2026 [parent_slug] => [catslug] => 34:latest-news [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

In March, we will officially leave the dark days of winter behind us. The spring (or vernal) equinox falls on 20 March, marking the point in Earth’s orbit where neither hemisphere will be tilted toward or away from the sun. This means we’ll experience an equally long day and night. More daylight is certainly cause for celebration, but so are the multitude of March sky offerings, including new constellations, a lunar eclipse visible to nearly a third of the world’s population, and galaxies galore!

)

What's Up? February 2026

February may be short, but the winter nights are still long and packed with sky-watching treats. From bright winter star patterns and the beautiful Beehive Cluster to dazzling planets, and even the chance of a comet! There’s plenty for naked-eye observers and telescope users to enjoy this month.

Read Time

6 minutes

February may be short, but the winter nights are still long and packed with sky-watching treats. From bright winter star patterns and the beautiful Beehive Cluster to dazzling planets, and even the chance of a comet! There’s plenty for naked-eye observers and telescope users to enjoy this month.

[fulltext] =>

The month may be short, but the nights are still long so it’s a great time to get out and look up. This month we have planets, galaxies, and potentially a comet for telescope users.

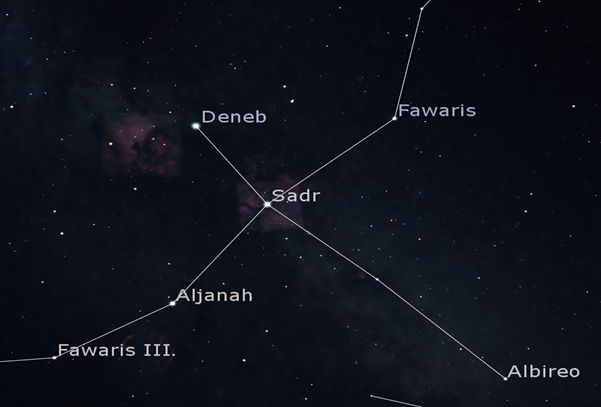

Constellations

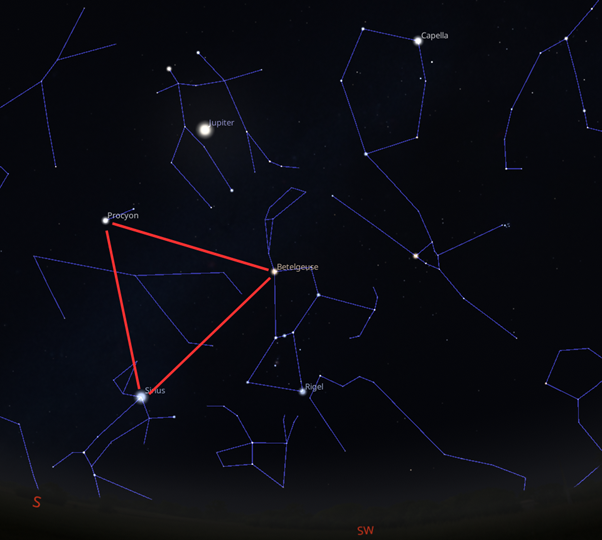

It’s still winter, so looking up we have the usual suspects, like Orion, dominating the night sky providing several brilliantly bright stars. In the past we have talked about the Summer Triangle, an asterism created from Vega (in Lyra), Deneb (in Cygnus), and Altair (in Aquila) which sits high in the sky throughout the Summer months. To compliment this, there is also a Winter Triangle consisting of Sirius (Canis Major), Procyon (Canis Minor) and Betelgeuse (Orion), three of the brightest stars in the winter night sky.

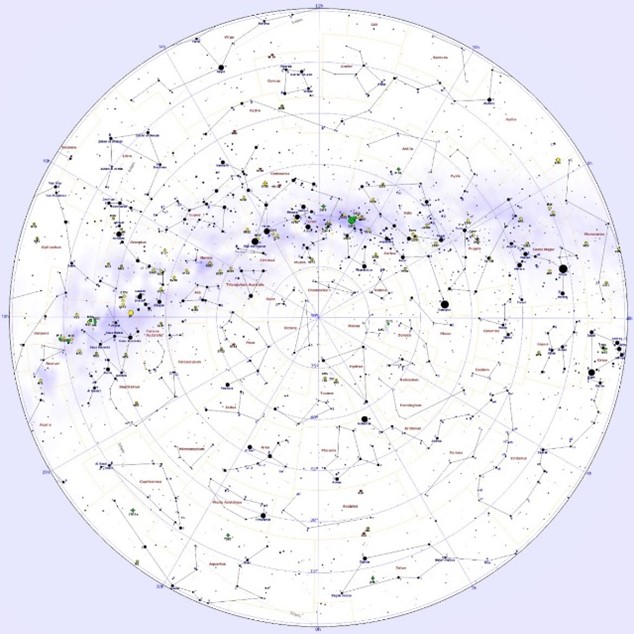

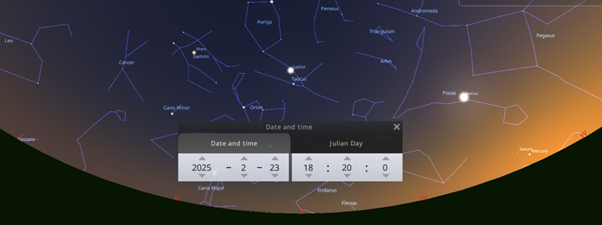

The night sky as seen on the 14th February at 2200 from Kielder Observatory, simulated on Stellarium. The asterism known as the Winter Triangle is marked out.Credit: Stellarium

However, if 3 stars isn’t enough for you, there is also the Winter Hexagon of Sirius (Canis Major), Procyon (Canis Minor), Pollux (Gemini), Capella (Auriga), Aldebaran (Taurus), and Rigel (Orion).

The night sky as seen on the 14th February at 2200 from Kielder Observatory, simulated on Stellarium. The asterism known as the Winter Hexagon is marked out. Credit: Stellarium

Asterisms like this can be a good way to boost your night sky knowledge, if you are learning how to spot the constellations they give you bright target stars to look out for. February is a great month to try and spot these stars because all of them are above the horizon for the full duration of the night. They are all also bright enough to be seen in light pollution, whether that’s natural light pollution from the Moon or artificial light pollution from street lights and the such. So really – there’s no excuse.

Object of the Month – The Beehive (M44)

I consider Cancer to be one of the more difficult constellations to spot in the sky. Although it inhabits a high position through dark winter and spring months, the stars that make up the crab are pretty faint and difficult to pick out. The brightest star, Tarf, has a visual magnitude of +3.5 which makes it the 297th brightest star in the sky. Because of this, it is often easier to find Cancer by not looking for it’s stars, but rather it’s brightest cluster – The Beehive!

The Beehive cluster, also known as M44, is a bright open cluster that has been known about since ancient times. Claudius Ptolemy described it as a “nebulous mass in the breast of Cancer” and that is a pretty apt description. Historically the description of “nebulous” was applied much more widely than today to describe anything that appeared fuzzy, foggy, or cloud-like, and so in older texts you will find it applied to clusters, nebulas, and galaxies alike. It is, as the observation by Ptolemy suggests, visible to the naked eye but it is fairly faint and so you will see it best out of the corner of your eye, an old trick in astronomy known as “averted vision”.

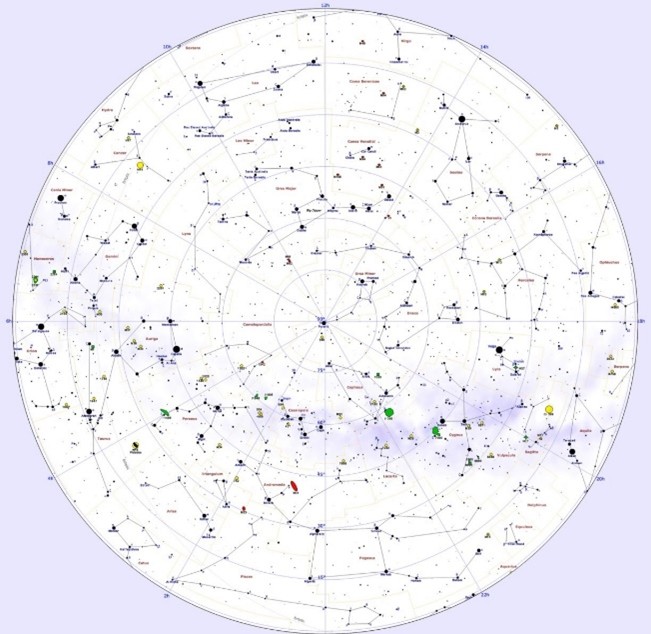

To find it, I would suggest locating the brighter constellations of Leo and Gemini, and then letting your eye wander between the two until something catches it. Or, if you want something more precise, draw a line between Castor and Regulus and the Beehive should sit roughly below the mid-point.

Leo, Cancer, and Gemini in a row. The Beehive Cluster is marked in Cancer by a ring of yellow dots and it sat mid-way between Leo and Gemini. Credit: Stellarium

The cluster is thought to be made up of 1000 stars believed to be all around 600 million years old and it is located around 600 light years away. It was one of the first objects studied by Galileo Galilei with his telescope in 1609 and looking at the cluster he was able to resolve 40 stars.

M44, the Beehive Cluster. Credit: Sauro Gaudenzi 7 Data Telescope Live

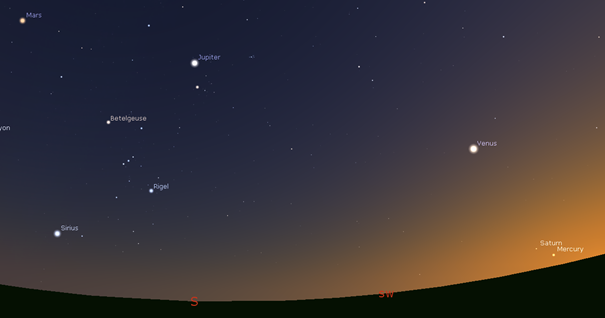

Planets

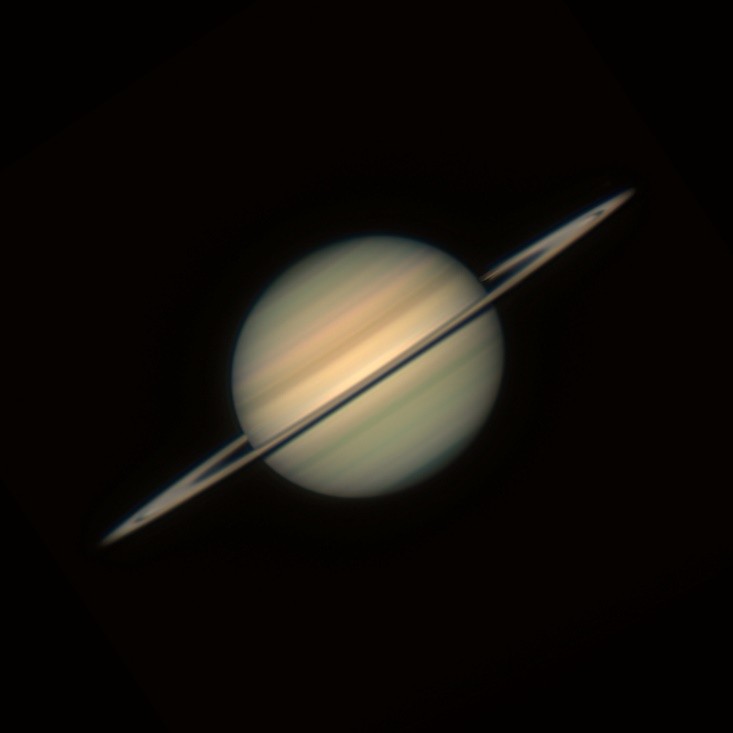

This is the last chance you have to see Saturn for a few months as it approaches the Sun, but as it emerges from the other side in April it will only be visible for a short time in the pre-dawn sky. It will them get better as it moves further from the glare of our closest star, but you’ll be waiting months for that! If you’ve missed Saturn so far this winter, look for it towards the West as it gets dark and it will be the brightest “star” visible fairly low to the horizon.

Jupiter will continue to stun as it sits high up in the sky in the constellation of Gemini, turning the twins into triplets. It will be visible all night from sunset to sunrise.

Towards the end of the month on the 19th Mercury will reach it’s greatest east elongation from the Sun, which means that it will be visible in the sky shortly after sunset. On the 20th it will be at its highest altitude in the evening sky. Being the closest planet to the Sun, Mercury always follows or leads close to the Sun in our sky making it one of the trickier planets to observe, this could be your chance! In fact, for those who are able to find a low enough western horizon there is a chance to see a mini-planetary parade with Mercury, Venus, and Saturn all clustered together in the west shortly after sunset and Jupiter in the south east.

The sky from Kielder Observatory on the 23rd February at 1805 looking south, simulated on Stellarium. Credit: Stellarium

The Moon

Full Moon: 1st February

Last Quarter: 9th February

New Moon: 17th February

First Quarter: 24th February

Antarctic Annular Eclipse

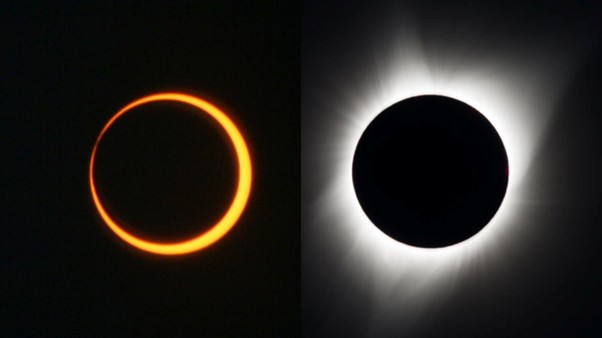

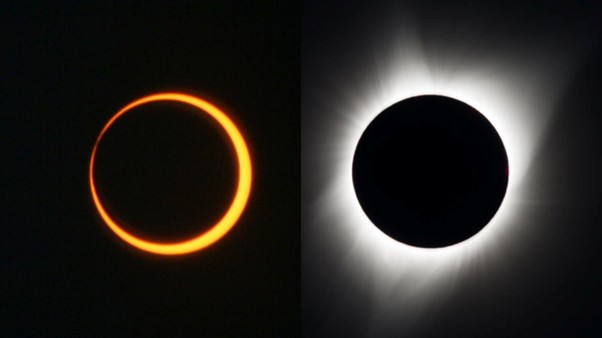

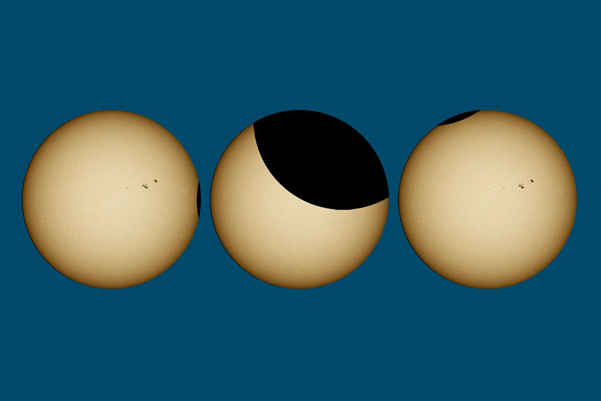

An annular solar eclipse (left) vs a total solar eclipse (right). Credit: NASA/Bill Dunford, left, and NASA/Aubrey Gemignani, right

I think it’s fairly unlikely that anyone reading this finds themselves planning to be in Antarctica this February, but in the off chance that someone’s got plans that way I feel obliged to inform them of the annular solar eclipse which will be visible on the 17th February around midday.

A solar eclipse occurs as the Moon passes between the Earth and the Sun, obscuring part or all of the Sun in the process. An annular solar eclipse, sometimes called a “ring of fire” eclipse, occurs when the Moon passes completely between the Earth and the Sun while the Moon is at apogee (the most distant point in its elliptical orbit around the Earth). When this happens, the Moon appears to be slightly smaller than the Sun and so as it blocks the centre, a small ring of light can still be seen around the edge.

[checked_out] => 0 [checked_out_time] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [catid] => 34 [created] => 2026-01-27 12:37:24 [created_by] => 72927 [created_by_alias] => [modified] => 2026-01-27 12:39:14 [modified_by] => 72927 [modified_by_name] => Lindsey Brown [publish_up] => 2026-01-27 12:37:29 [publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [images] => {"image_intro":"images\/whatsup\/WUFEB7.jpg","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [urls] => {"urla":false,"urlatext":"","targeta":"","urlb":false,"urlbtext":"","targetb":"","urlc":false,"urlctext":"","targetc":""} [attribs] => {"show_title":"","link_titles":"","show_tags":"","show_intro":"","info_block_position":"","info_block_show_title":"","show_category":"","link_category":"","show_parent_category":"","link_parent_category":"","show_author":"","link_author":"","show_create_date":"","show_modify_date":"","show_publish_date":"","show_item_navigation":"","show_icons":"","show_print_icon":"","show_email_icon":"","show_vote":"","show_hits":"","show_noauth":"","urls_position":"","alternative_readmore":"","article_layout":"","show_publishing_options":"","show_article_options":"","show_urls_images_backend":"","show_urls_images_frontend":""} [metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"","rights":"","xreference":""} [metakey] => [metadesc] => [access] => 1 [hits] => 1382 [xreference] => [featured] => 0 [language] => * [readmore] => 8347 [state] => 1 [category_title] => Latest News [category_route] => uncategorised/latest-news [category_access] => 1 [category_alias] => latest-news [author] => Lindsey Brown [author_email] => lindsey@kielderobservatory.org [parent_title] => ROOT [parent_id] => 1 [parent_route] => [parent_alias] => root [rating] => [rating_count] => [published] => 1 [parents_published] => 1 [alternative_readmore] => [layout] => [params] => Joomla\Registry\Registry Object ( [data:protected] => stdClass Object ( [article_layout] => _:default [show_title] => 1 [link_titles] => 0 [show_intro] => 1 [info_block_position] => 0 [info_block_show_title] => 0 [show_category] => 0 [link_category] => 0 [show_parent_category] => 0 [link_parent_category] => 0 [show_author] => 0 [link_author] => 0 [show_create_date] => 0 [show_modify_date] => 0 [show_publish_date] => 0 [show_item_navigation] => 0 [show_vote] => 0 [show_readmore] => 1 [show_readmore_title] => 0 [readmore_limit] => 100 [show_tags] => 0 [show_icons] => 0 [show_print_icon] => 0 [show_email_icon] => 0 [show_hits] => 0 [show_noauth] => 0 [urls_position] => 0 [show_publishing_options] => 1 [show_article_options] => 1 [save_history] => 1 [history_limit] => 10 [show_urls_images_frontend] => 0 [show_urls_images_backend] => 1 [targeta] => 0 [targetb] => 0 [targetc] => 0 [float_intro] => right [float_fulltext] => none [category_layout] => _:blog [show_category_heading_title_text] => 1 [show_category_title] => 0 [show_description] => 1 [show_description_image] => 0 [maxLevel] => 1 [show_empty_categories] => 0 [show_no_articles] => 1 [show_subcat_desc] => 1 [show_cat_num_articles] => 0 [show_cat_tags] => 1 [show_base_description] => 1 [maxLevelcat] => -1 [show_empty_categories_cat] => 0 [show_subcat_desc_cat] => 1 [show_cat_num_articles_cat] => 1 [num_leading_articles] => 0 [num_intro_articles] => 27 [num_columns] => 1 [num_links] => 4 [multi_column_order] => 0 [show_subcategory_content] => 0 [show_pagination_limit] => 1 [filter_field] => hide [show_headings] => 1 [list_show_date] => 0 [date_format] => [list_show_hits] => 1 [list_show_author] => 1 [orderby_pri] => order [orderby_sec] => rdate [order_date] => published [show_pagination] => 1 [show_pagination_results] => 1 [show_featured] => show [show_feed_link] => 1 [feed_summary] => 0 [feed_show_readmore] => 0 [show_page_heading] => 0 [layout_type] => blog [menu_text] => 1 [menu_show] => 0 [secure] => 0 [page_title] => Latest News [page_description] => Kielder Observatory Astronomical Society [page_rights] => [robots] => [access-view] => 1 ) [separator] => . ) [displayDate] => 2026-01-27 12:37:24 [slug] => 487:what-s-up-february-2026 [parent_slug] => [catslug] => 34:latest-news [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

February may be short, but the winter nights are still long and packed with sky-watching treats. From bright winter star patterns and the beautiful Beehive Cluster to dazzling planets, and even the chance of a comet! There’s plenty for naked-eye observers and telescope users to enjoy this month.

)

What's Up? January 2026

January’s long, dark nights are perfect for stargazing. From the story of Gemini the Twins and a New Year meteor shower to Jupiter at its brightest, rare planet groupings, and beautiful Moon encounters, the winter sky is full of wonders waiting to be explored.

New Year, new skies! Discover what wonders await in January’s night sky.

Read Time

6 minutes

January’s long, dark nights are perfect for stargazing. From the story of Gemini the Twins and a New Year meteor shower to Jupiter at its brightest, rare planet groupings, and beautiful Moon encounters, the winter sky is full of wonders waiting to be explored.

New Year, new skies! Discover what wonders await in January’s night sky.

[fulltext] =>

What’s up January 2026

January Skies bring long nights, with the sun setting by 4pm most of the month. Perfect for getting out star gazing! Here’s what’s up this month.

Constellations:

We always focus on Orion, the most famous winter constellation so this month I thought it would be nice to discuss a slightly different winter constellation: Gemini the Twins. This month Jupiter has joined them in the sky so I thought this would be a great chance to learn what this constellation is. Gemini made up of a set of twins from ancient Greek mythology. Castor and Pollux were members of the argonauts, the band of Greek heroes who went with Jason to retrieve the golden fleece. The twins have the same mother Queen Leda of Sparta but different fathers. Castor’s father was King Tyndareus whilst Pollux was sired by Zeus; the king of the Greek gods. As viewed from the northern hemisphere Pollux is the lower star in the twins. Throughout January Gemini will appear in the east at sunset and rise higher into the sky before setting just before sunrise in the west. The constellation is completely opposite the Sun right now. As one of the Zodiac signs it is one of the 12 that the sun traces through, so in 6 months in July the Sun will be in Gemini. This is why someone born in summer may have Gemini as their star sign. Your star sign is whichever constellation the sun is in the day you are born; making the best time to actually see your star sign in the sky 6 months after your birthday!

Figure 1: Gemini at 18:30 on January 23rd. See how it is positioned near Orion and the small dog Canis minor below. It is easy to confuse Canis minor and the Gemini twins. Remember the twins are closer in brightness to each other whilst Canis minor has one very bright star, Procyon, and a dimmer star Gomeisa. The very bright object in Pollux’s hip in Jupiter.

Meteor Showers:

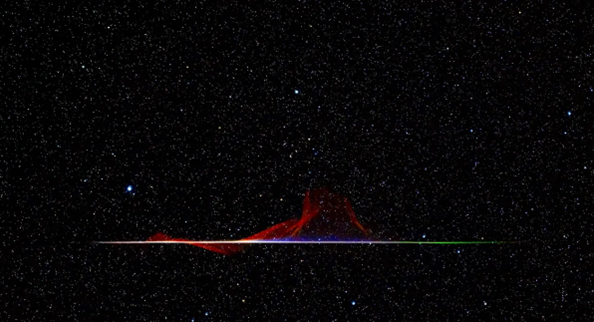

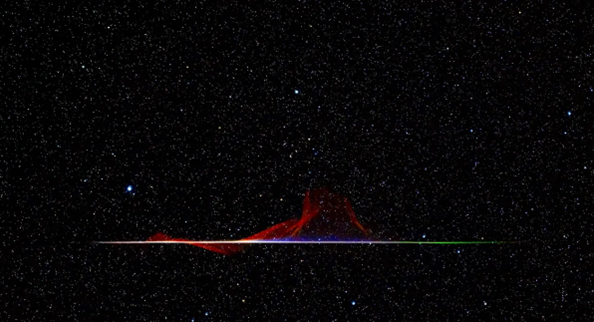

Figure 2: A colourful Quadrantid meteor by Frank Kusaj, winner of the Astronomy Photographer of the year 2021.

On January 3rd-4th the Quadrantids meteor shower peaks. However, this is a pretty poor chance to get a bit of luck for the new year as it falls on full moon night which will cause a lot of natural light pollution, making it difficult to catch weak flashes of blue light streaking across the sky. It is a fairly good hourly rate of shooting stars, with the maximum being 120 meteors per hour during the peak of the shower, but this only last a few hours. Remember that is in reference to the best scenario: dark, clear night conditions. So even with a full moon it might still be worth a few hours sat out with a blanket and mug of hot chocolate and welcome in the new year with a bit of stargazing magic.

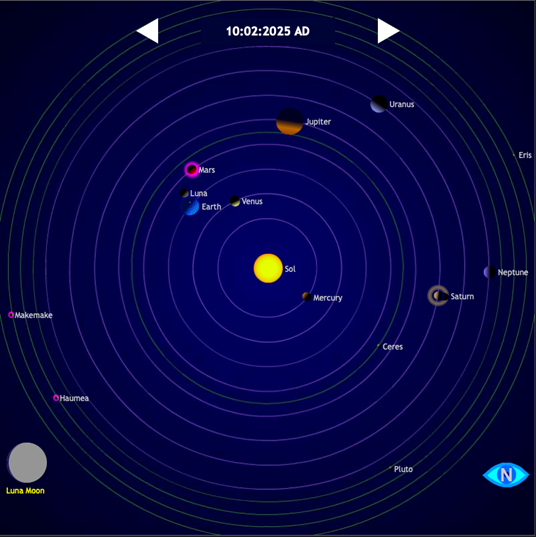

Planets:

This month we do have all the Gas Giants ganging up in the sky, but Jupiter is the brightest and it is at its best, reaching opposition on the 10th. Opposition means that it is directly opposite the sun so appears lit up at its best for us. It takes around 13 months for Jupiter to go back to opposition so this is the best brightness until February 2026!

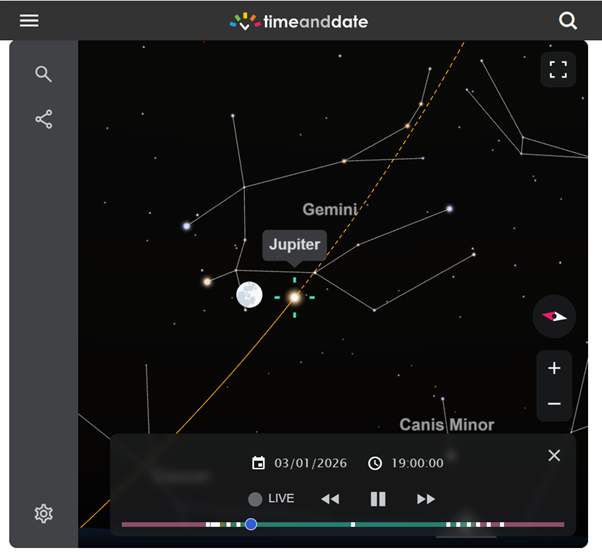

Figure 3: Taken from timeanddate.com. January 3rd position of the Full moon and Jupiter in the constellation Gemini.

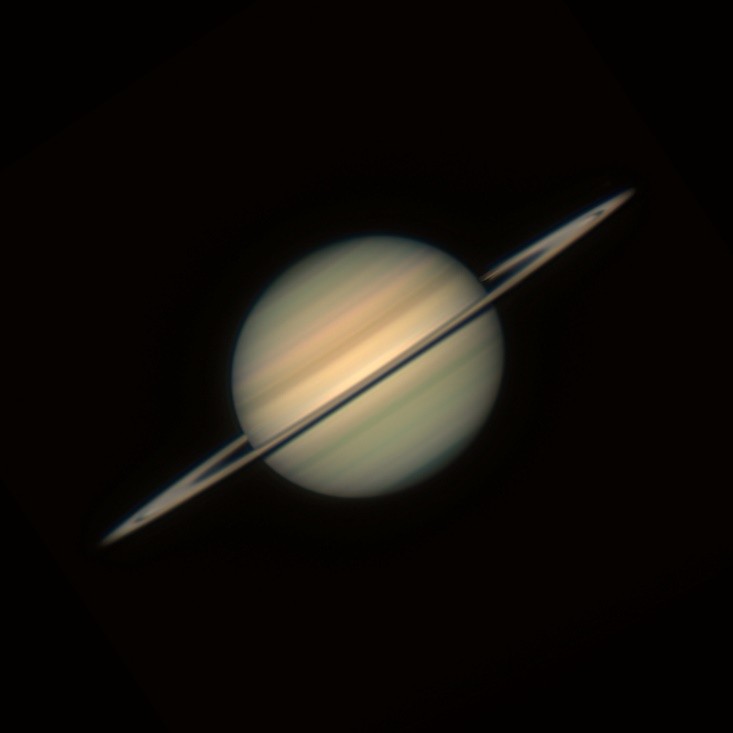

Saturn is also in the sky this month, visible in the early evening over the south. Remember planets do not twinkle, stars do! So use that to check that the brightest point of light you think is a planet really is a planet. This is because planets are closer to us, within our solar system whilst other stars are far beyond the reaches of our solar system, dotted across our galaxy. Planets appear bigger and brighter on the sky, unless they are Neptune and Uranus which are dimmer and need binoculars or a telescope to be seen by our weak human eyes.

The two blue gas giants will appear as iridescent blue dots, compared to the shinier twinkling white stars that surround them, I like to think the comparison is the same as a diamond and a pearl, the stars being diamonds and the planets being pearls.

Neptune will be right above Saturn throughout the month, so if you can find Saturn you can use it as a stepping stone to finding Neptune. Uranus is a bit of a harder spot, situated in the constellation of Taurus the Bull, underneath the Pleiades cluster, the heart of the Bull.

Moon:

The moon is in some excellent viewing and picture-perfect spots this month:

On the 3rd of January the moon and Jupiter will be close together in Gemini, and on the 23rd the moon will be hanging out with Saturn and Neptune sandwiched between them in a traffic like stack. On the 30th the moon catches up with Jupiter again so a second chance at a Gemini-Jupiter-Moon shot, though this time the moon will be only 92% full, so a tiny sliver of the terminator line will be present on the edge. This will be a truly beautiful sight and an easy to point the telescope in the right direction night.

Figure 4: Moon, Neptune, and Saturn on the 23rd of January in the evening sky after sunset. Taken from timeanddate.com

3rd: Full moon

10th: Half-moon :Third quarter

18th: New moon

26th: Half-moon: First quarter

January’s Dull moon is called the “Wolf moon”. This is thought to have old Celtic and English origins from when wolves ran wild through our wilderness, some of the only nature still visible in the cold deep winter. Hopefully you don’t come across a wolf at full moon this month!

As always, wrap up warm, give your eyes time to adjust to the dark, and enjoy the winter sky. Clears Skies and Happy Stargazing!

[checked_out] => 0 [checked_out_time] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [catid] => 34 [created] => 2025-12-22 21:40:39 [created_by] => 72927 [created_by_alias] => [modified] => 2025-12-22 22:14:24 [modified_by] => 72927 [modified_by_name] => Lindsey Brown [publish_up] => 2025-12-22 21:40:39 [publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [images] => {"image_intro":"images\/whatsup\/JAN262.png","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [urls] => {"urla":false,"urlatext":"","targeta":"","urlb":false,"urlbtext":"","targetb":"","urlc":false,"urlctext":"","targetc":""} [attribs] => {"show_title":"","link_titles":"","show_tags":"","show_intro":"","info_block_position":"","info_block_show_title":"","show_category":"","link_category":"","show_parent_category":"","link_parent_category":"","show_author":"","link_author":"","show_create_date":"","show_modify_date":"","show_publish_date":"","show_item_navigation":"","show_icons":"","show_print_icon":"","show_email_icon":"","show_vote":"","show_hits":"","show_noauth":"","urls_position":"","alternative_readmore":"","article_layout":"","show_publishing_options":"","show_article_options":"","show_urls_images_backend":"","show_urls_images_frontend":""} [metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"","rights":"","xreference":""} [metakey] => [metadesc] => [access] => 1 [hits] => 3451 [xreference] => [featured] => 0 [language] => * [readmore] => 6802 [state] => 1 [category_title] => Latest News [category_route] => uncategorised/latest-news [category_access] => 1 [category_alias] => latest-news [author] => Lindsey Brown [author_email] => lindsey@kielderobservatory.org [parent_title] => ROOT [parent_id] => 1 [parent_route] => [parent_alias] => root [rating] => [rating_count] => [published] => 1 [parents_published] => 1 [alternative_readmore] => [layout] => [params] => Joomla\Registry\Registry Object ( [data:protected] => stdClass Object ( [article_layout] => _:default [show_title] => 1 [link_titles] => 0 [show_intro] => 1 [info_block_position] => 0 [info_block_show_title] => 0 [show_category] => 0 [link_category] => 0 [show_parent_category] => 0 [link_parent_category] => 0 [show_author] => 0 [link_author] => 0 [show_create_date] => 0 [show_modify_date] => 0 [show_publish_date] => 0 [show_item_navigation] => 0 [show_vote] => 0 [show_readmore] => 1 [show_readmore_title] => 0 [readmore_limit] => 100 [show_tags] => 0 [show_icons] => 0 [show_print_icon] => 0 [show_email_icon] => 0 [show_hits] => 0 [show_noauth] => 0 [urls_position] => 0 [show_publishing_options] => 1 [show_article_options] => 1 [save_history] => 1 [history_limit] => 10 [show_urls_images_frontend] => 0 [show_urls_images_backend] => 1 [targeta] => 0 [targetb] => 0 [targetc] => 0 [float_intro] => right [float_fulltext] => none [category_layout] => _:blog [show_category_heading_title_text] => 1 [show_category_title] => 0 [show_description] => 1 [show_description_image] => 0 [maxLevel] => 1 [show_empty_categories] => 0 [show_no_articles] => 1 [show_subcat_desc] => 1 [show_cat_num_articles] => 0 [show_cat_tags] => 1 [show_base_description] => 1 [maxLevelcat] => -1 [show_empty_categories_cat] => 0 [show_subcat_desc_cat] => 1 [show_cat_num_articles_cat] => 1 [num_leading_articles] => 0 [num_intro_articles] => 27 [num_columns] => 1 [num_links] => 4 [multi_column_order] => 0 [show_subcategory_content] => 0 [show_pagination_limit] => 1 [filter_field] => hide [show_headings] => 1 [list_show_date] => 0 [date_format] => [list_show_hits] => 1 [list_show_author] => 1 [orderby_pri] => order [orderby_sec] => rdate [order_date] => published [show_pagination] => 1 [show_pagination_results] => 1 [show_featured] => show [show_feed_link] => 1 [feed_summary] => 0 [feed_show_readmore] => 0 [show_page_heading] => 0 [layout_type] => blog [menu_text] => 1 [menu_show] => 0 [secure] => 0 [page_title] => Latest News [page_description] => Kielder Observatory Astronomical Society [page_rights] => [robots] => [access-view] => 1 ) [separator] => . ) [displayDate] => 2025-12-22 21:40:39 [slug] => 485:what-s-up-january-2026 [parent_slug] => [catslug] => 34:latest-news [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

January’s long, dark nights are perfect for stargazing. From the story of Gemini the Twins and a New Year meteor shower to Jupiter at its brightest, rare planet groupings, and beautiful Moon encounters, the winter sky is full of wonders waiting to be explored.

New Year, new skies! Discover what wonders await in January’s night sky.

)

What's Up? December 2025

The long winter nights are here, and while most people head indoors, stargazers know this is the best time to look up. December brings some of the brightest treats of the year, from the Geminid meteor shower to the return of Orion, shimmering planets, and even a Cold Supermoon.

There’s plenty to unwrap in the night sky this festive season…

Image credit: Sky & Telescope

Read Time

3 minutes

The long winter nights are here, and while most people head indoors, stargazers know this is the best time to look up. December brings some of the brightest treats of the year, from the Geminid meteor shower to the return of Orion, shimmering planets, and even a Cold Supermoon.

There’s plenty to unwrap in the night sky this festive season…

Image credit: Sky & Telescope

[fulltext] =>

The long dark winter nights are closing in and while some may recoil indoors, star gazers rejoice as this brings more opportunities to connect with the night sky. There’s plenty to see on the run up to Christmas with many gifts from the universe on display. Let’s take a look at what to expect this festive season.

Meteor Showers

For an early Christmas treat the Geminid meteor shower peaks on December 13th-14th and is considered one of the best meteor showers of the year due to their high frequency coupled with dark winter skies. This shower occurs when Earth intersects the dust cloud left by the asteroid 3200 Phaethon and, unlike most other meteor showers, this event originates from an asteroid rather than a comet. Observers can expect to see up to 120 meteors per hour appearing to radiate from the constellation Gemini.

Image Credit: Sky and Telescope

Constellation spotlight: Orion

Image Credit: Sky and Telescope

The constellation of Orion is a spectacular sight at this time of year, a classic and prominent set of stars visible during winter in the northern hemisphere. Named after a hunter in ancient Greek mythology, it’s reappearance at this time reminds us the long nights are closing in while the skies come alive.

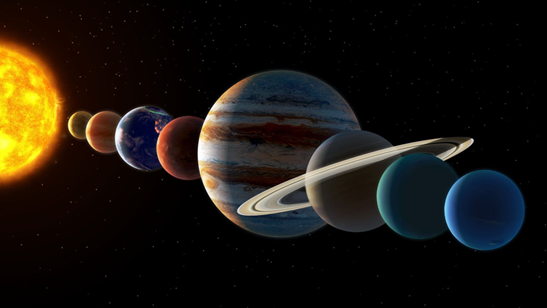

Planets

Visible to the naked eye and amazing in appearance through a small telescope, or even binoculars, are the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn (positions in the sky during a mid-December evening shown below).

Screenshot: Stellarium

Moon

On December 4th we have a ‘Cold Supermoon’ which will appear larger and brighter than usual due to its proximity to Earth. The description of ‘cold’ refers to a full moon occurring at the coldest time of the year, typically in December. This marks the last supermoon until November 2026.

Image credit: Space.com

International Space Station

Image credit: Space.com

If you look skyward beginning in the west and moving south low on the horizon commencing 17.22pm December 4th you will be treated with a glimpse of the International Space Station, aka Santa, delivering the latest astronomical goodies we’ve all been waiting for!

We wish you a Merry Christmas, a Happy New Year and very clear skies!

[checked_out] => 0 [checked_out_time] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [catid] => 34 [created] => 2025-11-27 12:56:22 [created_by] => 72927 [created_by_alias] => [modified] => 2026-01-27 12:39:35 [modified_by] => 72927 [modified_by_name] => Lindsey Brown [publish_up] => 2025-11-27 12:56:22 [publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [images] => {"image_intro":"images\/WUD1.jpg","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [urls] => {"urla":false,"urlatext":"","targeta":"","urlb":false,"urlbtext":"","targetb":"","urlc":false,"urlctext":"","targetc":""} [attribs] => {"show_title":"","link_titles":"","show_tags":"","show_intro":"","info_block_position":"","info_block_show_title":"","show_category":"","link_category":"","show_parent_category":"","link_parent_category":"","show_author":"","link_author":"","show_create_date":"","show_modify_date":"","show_publish_date":"","show_item_navigation":"","show_icons":"","show_print_icon":"","show_email_icon":"","show_vote":"","show_hits":"","show_noauth":"","urls_position":"","alternative_readmore":"","article_layout":"","show_publishing_options":"","show_article_options":"","show_urls_images_backend":"","show_urls_images_frontend":""} [metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"","rights":"","xreference":""} [metakey] => [metadesc] => [access] => 1 [hits] => 1017 [xreference] => [featured] => 0 [language] => * [readmore] => 3629 [state] => 1 [category_title] => Latest News [category_route] => uncategorised/latest-news [category_access] => 1 [category_alias] => latest-news [author] => Lindsey Brown [author_email] => lindsey@kielderobservatory.org [parent_title] => ROOT [parent_id] => 1 [parent_route] => [parent_alias] => root [rating] => [rating_count] => [published] => 1 [parents_published] => 1 [alternative_readmore] => [layout] => [params] => Joomla\Registry\Registry Object ( [data:protected] => stdClass Object ( [article_layout] => _:default [show_title] => 1 [link_titles] => 0 [show_intro] => 1 [info_block_position] => 0 [info_block_show_title] => 0 [show_category] => 0 [link_category] => 0 [show_parent_category] => 0 [link_parent_category] => 0 [show_author] => 0 [link_author] => 0 [show_create_date] => 0 [show_modify_date] => 0 [show_publish_date] => 0 [show_item_navigation] => 0 [show_vote] => 0 [show_readmore] => 1 [show_readmore_title] => 0 [readmore_limit] => 100 [show_tags] => 0 [show_icons] => 0 [show_print_icon] => 0 [show_email_icon] => 0 [show_hits] => 0 [show_noauth] => 0 [urls_position] => 0 [show_publishing_options] => 1 [show_article_options] => 1 [save_history] => 1 [history_limit] => 10 [show_urls_images_frontend] => 0 [show_urls_images_backend] => 1 [targeta] => 0 [targetb] => 0 [targetc] => 0 [float_intro] => right [float_fulltext] => none [category_layout] => _:blog [show_category_heading_title_text] => 1 [show_category_title] => 0 [show_description] => 1 [show_description_image] => 0 [maxLevel] => 1 [show_empty_categories] => 0 [show_no_articles] => 1 [show_subcat_desc] => 1 [show_cat_num_articles] => 0 [show_cat_tags] => 1 [show_base_description] => 1 [maxLevelcat] => -1 [show_empty_categories_cat] => 0 [show_subcat_desc_cat] => 1 [show_cat_num_articles_cat] => 1 [num_leading_articles] => 0 [num_intro_articles] => 27 [num_columns] => 1 [num_links] => 4 [multi_column_order] => 0 [show_subcategory_content] => 0 [show_pagination_limit] => 1 [filter_field] => hide [show_headings] => 1 [list_show_date] => 0 [date_format] => [list_show_hits] => 1 [list_show_author] => 1 [orderby_pri] => order [orderby_sec] => rdate [order_date] => published [show_pagination] => 1 [show_pagination_results] => 1 [show_featured] => show [show_feed_link] => 1 [feed_summary] => 0 [feed_show_readmore] => 0 [show_page_heading] => 0 [layout_type] => blog [menu_text] => 1 [menu_show] => 0 [secure] => 0 [page_title] => Latest News [page_description] => Kielder Observatory Astronomical Society [page_rights] => [robots] => [access-view] => 1 ) [separator] => . ) [displayDate] => 2025-11-27 12:56:22 [slug] => 484:what-s-up-december-2026 [parent_slug] => [catslug] => 34:latest-news [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

The long winter nights are here, and while most people head indoors, stargazers know this is the best time to look up. December brings some of the brightest treats of the year, from the Geminid meteor shower to the return of Orion, shimmering planets, and even a Cold Supermoon.

There’s plenty to unwrap in the night sky this festive season…

Image credit: Sky & Telescope

)

What's Up? November 2025

Stargazing season is here! With longer nights and clear skies, November brings the Leonid meteor shower (peaking 17–18 November) and stunning views of Jupiter, Saturn, and even distant Uranus and Neptune.

Discover the best times to look up, moon phase dates, and what else to spot in this month’s night sky by reading our monthly What's Up? Guide.

Read Time

3 minutes

Stargazing season is here! With longer nights and clear skies, November brings the Leonid meteor shower (peaking 17–18 November) and stunning views of Jupiter, Saturn, and even distant Uranus and Neptune.

Discover the best times to look up, moon phase dates, and what else to spot in this month’s night sky by reading our monthly What's Up? Guide.

[fulltext] =>

It’s truly stargazing season, the clocks have gone back and now you can star gaze all evening and still go to sleep at a decent time! Let’s have a look at what to expect this month:

Meteor showers

Leonid’s peak 17th-18th November

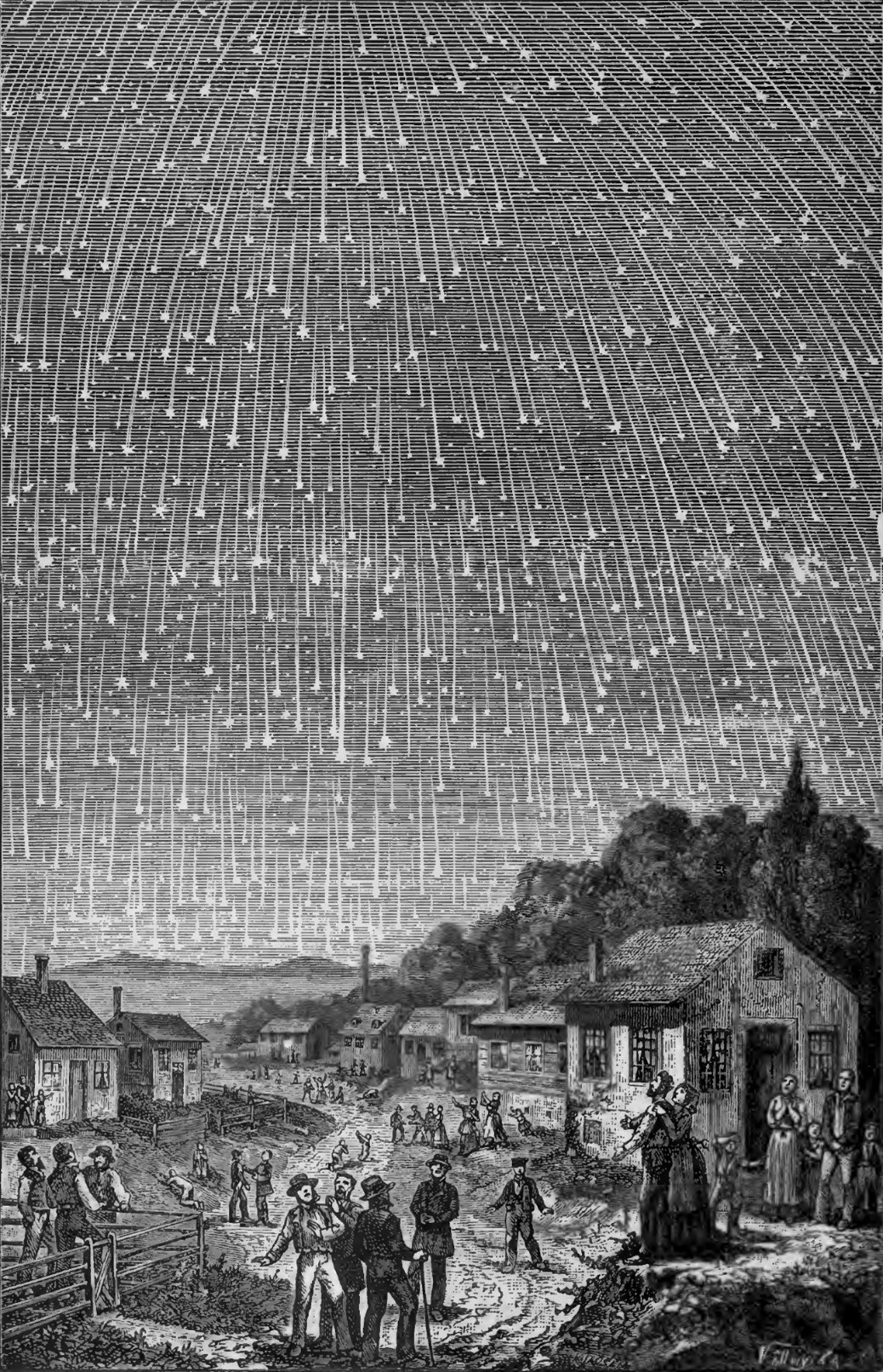

This meteor shower was historically one of the most spectacular to grace our skies in 1883. Well Americas skies. Europe was not in line of sight for the shooting star show. Depictions of it give the idea of a sparkling rain storm. However now a days we get maybe 10-15 per hour. A roar turned to a whimper. Meteor showers, as is shooting stars scientific name, are caused Earth orbiting into trails of debris left by Comet tails. Comets are these huge dirty snowballs, made of dirt and ice that orbit round our solar system. Sometimes they take decades, sometime millennia to complete one orbit, all the while leaving a tail of leftovers as they go. If there is a large deposit of even sand size particles, those can cause bright flashes of light when they are attracted to Earth and hit our atmosphere. Back in 1883 there must have been a huge deposit from what we now know was Comet Tempel-Tuttle.

Fig 1: A depiction of the Leonids over America in 1883. Drawing published in 1888 based on eye witness accounts.

Planets

Figure 2. Screenshot taken from Stellarium of evening sky in mid-November, showing planet positions.

Saturn and Jupiter are both of great visibility throughout the month, Saturn rising first, bold in the mid to low southern sky most of the night and Jupiter following. If you can spot Orion you can use his shoulders as a good indicator towards the bright Gas Giants to the east and west. Uranus, whilst never visible to the naked eye, is right next to the Pleiades Cluster (also known as the seven sisters) so get those binoculars and telescopes out and see if you can catch it! It should look like a small blue dot underneath the cluster. Not as sparkly as the stars, but a solid iridescent dot. An extra addition: Neptune is hidden in that picture but is also hiding in the sky, just above and east of Saturn. Again a small blue dot compared to the whiter stars surrounding it. All the gas giants are available for the tick off stargazing list!

Moon Phases

5th: Full moon

11th: Half moon (Third quarter)

20th: New moon

27th: Half moon (First quarter)

Clears Skies and Happy Star-Gazing!

[checked_out] => 42928 [checked_out_time] => 2025-11-13 19:53:51 [catid] => 34 [created] => 2025-10-29 12:01:12 [created_by] => 72927 [created_by_alias] => [modified] => 2025-11-13 19:53:51 [modified_by] => 42928 [modified_by_name] => Dan Pye [publish_up] => 2025-10-29 12:01:12 [publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [images] => {"image_intro":"images\/WU-NOV-25-Picture2.jpg","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [urls] => {"urla":false,"urlatext":"","targeta":"","urlb":false,"urlbtext":"","targetb":"","urlc":false,"urlctext":"","targetc":""} [attribs] => {"show_title":"","link_titles":"","show_tags":"","show_intro":"","info_block_position":"","info_block_show_title":"","show_category":"","link_category":"","show_parent_category":"","link_parent_category":"","show_author":"","link_author":"","show_create_date":"","show_modify_date":"","show_publish_date":"","show_item_navigation":"","show_icons":"","show_print_icon":"","show_email_icon":"","show_vote":"","show_hits":"","show_noauth":"","urls_position":"","alternative_readmore":"","article_layout":"","show_publishing_options":"","show_article_options":"","show_urls_images_backend":"","show_urls_images_frontend":""} [metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"","rights":"","xreference":""} [metakey] => [metadesc] => [access] => 1 [hits] => 1607 [xreference] => [featured] => 0 [language] => * [readmore] => 3329 [state] => 1 [category_title] => Latest News [category_route] => uncategorised/latest-news [category_access] => 1 [category_alias] => latest-news [author] => Lindsey Brown [author_email] => lindsey@kielderobservatory.org [parent_title] => ROOT [parent_id] => 1 [parent_route] => [parent_alias] => root [rating] => [rating_count] => [published] => 1 [parents_published] => 1 [alternative_readmore] => [layout] => [params] => Joomla\Registry\Registry Object ( [data:protected] => stdClass Object ( [article_layout] => _:default [show_title] => 1 [link_titles] => 0 [show_intro] => 1 [info_block_position] => 0 [info_block_show_title] => 0 [show_category] => 0 [link_category] => 0 [show_parent_category] => 0 [link_parent_category] => 0 [show_author] => 0 [link_author] => 0 [show_create_date] => 0 [show_modify_date] => 0 [show_publish_date] => 0 [show_item_navigation] => 0 [show_vote] => 0 [show_readmore] => 1 [show_readmore_title] => 0 [readmore_limit] => 100 [show_tags] => 0 [show_icons] => 0 [show_print_icon] => 0 [show_email_icon] => 0 [show_hits] => 0 [show_noauth] => 0 [urls_position] => 0 [show_publishing_options] => 1 [show_article_options] => 1 [save_history] => 1 [history_limit] => 10 [show_urls_images_frontend] => 0 [show_urls_images_backend] => 1 [targeta] => 0 [targetb] => 0 [targetc] => 0 [float_intro] => right [float_fulltext] => none [category_layout] => _:blog [show_category_heading_title_text] => 1 [show_category_title] => 0 [show_description] => 1 [show_description_image] => 0 [maxLevel] => 1 [show_empty_categories] => 0 [show_no_articles] => 1 [show_subcat_desc] => 1 [show_cat_num_articles] => 0 [show_cat_tags] => 1 [show_base_description] => 1 [maxLevelcat] => -1 [show_empty_categories_cat] => 0 [show_subcat_desc_cat] => 1 [show_cat_num_articles_cat] => 1 [num_leading_articles] => 0 [num_intro_articles] => 27 [num_columns] => 1 [num_links] => 4 [multi_column_order] => 0 [show_subcategory_content] => 0 [show_pagination_limit] => 1 [filter_field] => hide [show_headings] => 1 [list_show_date] => 0 [date_format] => [list_show_hits] => 1 [list_show_author] => 1 [orderby_pri] => order [orderby_sec] => rdate [order_date] => published [show_pagination] => 1 [show_pagination_results] => 1 [show_featured] => show [show_feed_link] => 1 [feed_summary] => 0 [feed_show_readmore] => 0 [show_page_heading] => 0 [layout_type] => blog [menu_text] => 1 [menu_show] => 0 [secure] => 0 [page_title] => Latest News [page_description] => Kielder Observatory Astronomical Society [page_rights] => [robots] => [access-view] => 1 ) [separator] => . ) [displayDate] => 2025-10-29 12:01:12 [slug] => 474:what-s-up-november-2025 [parent_slug] => [catslug] => 34:latest-news [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

Stargazing season is here! With longer nights and clear skies, November brings the Leonid meteor shower (peaking 17–18 November) and stunning views of Jupiter, Saturn, and even distant Uranus and Neptune.

Discover the best times to look up, moon phase dates, and what else to spot in this month’s night sky by reading our monthly What's Up? Guide.

)

From Dark Skies to London: Kielder Observatory at New Scientist Live 2025

Ever wondered what the Milky Way looks like away from city lights? Kielder Observatory brought the magic of the night sky to London with telescopes, VR experiences, stunning astrophotography, and interactive activities - inspiring thousands to look up, explore, and protect our stars. Discover how we engaged curious minds of all ages and shared the wonder of the cosmos.

Read Time

3 minutes

Ever wondered what the Milky Way looks like away from city lights? Kielder Observatory brought the magic of the night sky to London with telescopes, VR experiences, stunning astrophotography, and interactive activities - inspiring thousands to look up, explore, and protect our stars. Discover how we engaged curious minds of all ages and shared the wonder of the cosmos.

[fulltext] =>

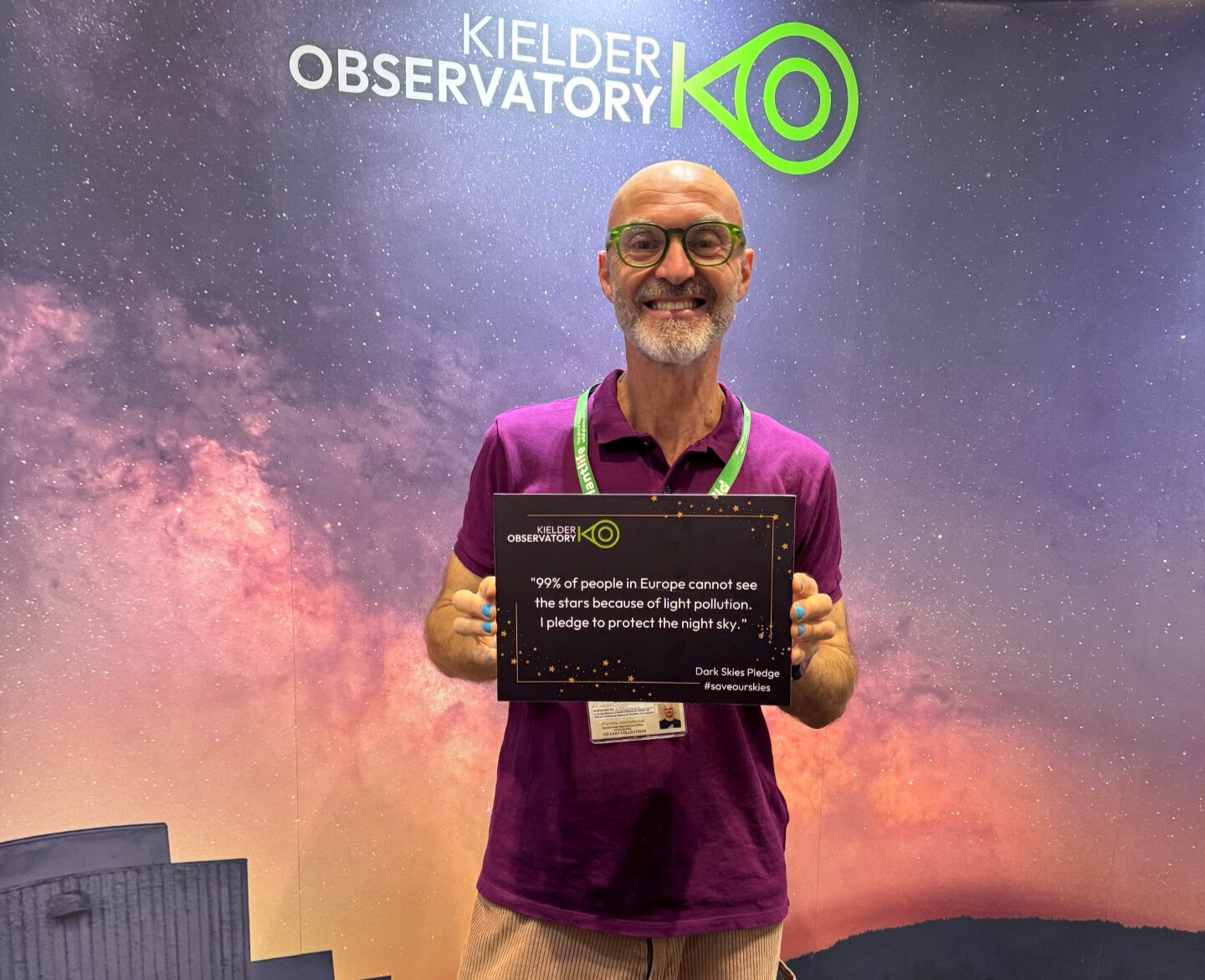

Kielder Observatory Shines at New Scientist Live 2025

Earlier this month, Kielder Observatory took to the stage at New Scientist Live 2025, the UK’s biggest festival of ideas and discovery, and what an incredible weekend it was!

We brought a little piece of Northumberland’s starry skies to London, giving attendees a taste of the wonder that awaits under truly dark skies. Our Dobsonian telescope, equipped with a digital eyepiece, showcased pre-recorded footage captured at our observatory - a mesmerising experience for many visitors who had never looked through a telescope before.

Throughout the weekend, our team enjoyed in-depth discussions with people passionate about the cosmos, sharing knowledge, stories, and inspiration about astronomy and our place in the universe.

We also gave attendees a glimpse into the future of astrophotography with the cutting-edge Seestar smart telescope, demonstrating how accessible capturing the night sky is becoming. Alongside this, we displayed a stunning collection of images taken from Kielder Observatory, including shots of the Aurora Borealis - which surprised many guests, who were amazed to learn that the northern lights can often be seen right here in the UK!

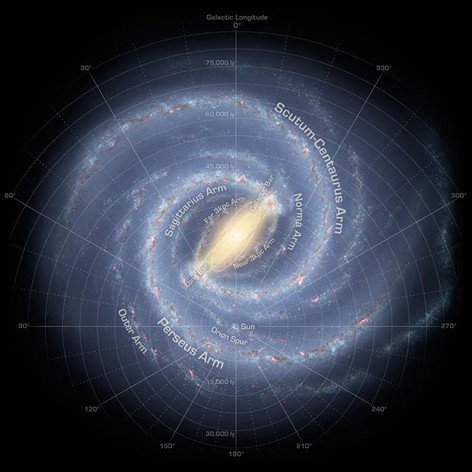

To highlight the importance of protecting our night skies, we invited visitors to take part in an interactive activity: three large boards featuring our signature image of the Milky Way - but with the stars removed. Guests were asked to “put the stars back in our sky” as a pledge to tackle light pollution. Many were shocked to learn that 99% of Europeans can no longer see the stars in great detail due to excessive artificial lighting.

Our VR experience was another big hit, allowing guests to explore what the night sky could look like from London if light pollution disappeared, an inspiring, immersive reminder of what we’re all missing.

On Schools Day, things got creative with origami star-making and a chance for students to write a question to an astronomer… or even an alien! The results were brilliant - keep an eye out for a future blog where we’ll share some of our favourites.

We couldn’t have done it without our fantastic team. Huge thanks to our volunteers who joined Lindsey, our Experience & Communications Coordinator, and Dan, our Director of Astronomy and Science Communication. Jo inspired visitors with her passion for our mission to spark curiosity and wonder in science. Alex guided guests through the constellations in our VR night sky safari, and Finn - a former Kielder astronomer now at the prestigious Greenwich Observatory - shared his expertise on our digital telescope.

Their enthusiasm and dedication truly captured what Kielder Observatory is all about: inspiring people to look up, discover, and protect our night skies.

We’re so proud of what we achieved and thrilled to have connected with so many new audiences who may never have experienced dark skies before. Hopefully, we’ve inspired a few more people to look up, and think differently about our universe and our place within it.

We hope to return to New Scientist Live in 2026, bigger, better, and continuing to bring the magic of the Kielder dark skies and astronomy to the public.

Learn more about the event, and maybe we will see you there next year! : live.newscientist.com

[checked_out] => 0 [checked_out_time] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [catid] => 34 [created] => 2025-10-24 16:27:33 [created_by] => 72927 [created_by_alias] => [modified] => 2025-10-24 16:31:28 [modified_by] => 72927 [modified_by_name] => Lindsey Brown [publish_up] => 2025-10-24 16:27:33 [publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [images] => {"image_intro":"images\/NSL19.jpg","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [urls] => {"urla":false,"urlatext":"","targeta":"","urlb":false,"urlbtext":"","targetb":"","urlc":false,"urlctext":"","targetc":""} [attribs] => {"show_title":"","link_titles":"","show_tags":"","show_intro":"","info_block_position":"","info_block_show_title":"","show_category":"","link_category":"","show_parent_category":"","link_parent_category":"","show_author":"","link_author":"","show_create_date":"","show_modify_date":"","show_publish_date":"","show_item_navigation":"","show_icons":"","show_print_icon":"","show_email_icon":"","show_vote":"","show_hits":"","show_noauth":"","urls_position":"","alternative_readmore":"","article_layout":"","show_publishing_options":"","show_article_options":"","show_urls_images_backend":"","show_urls_images_frontend":""} [metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"","rights":"","xreference":""} [metakey] => [metadesc] => [access] => 1 [hits] => 698 [xreference] => [featured] => 0 [language] => * [readmore] => 4600 [state] => 1 [category_title] => Latest News [category_route] => uncategorised/latest-news [category_access] => 1 [category_alias] => latest-news [author] => Lindsey Brown [author_email] => lindsey@kielderobservatory.org [parent_title] => ROOT [parent_id] => 1 [parent_route] => [parent_alias] => root [rating] => [rating_count] => [published] => 1 [parents_published] => 1 [alternative_readmore] => [layout] => [params] => Joomla\Registry\Registry Object ( [data:protected] => stdClass Object ( [article_layout] => _:default [show_title] => 1 [link_titles] => 0 [show_intro] => 1 [info_block_position] => 0 [info_block_show_title] => 0 [show_category] => 0 [link_category] => 0 [show_parent_category] => 0 [link_parent_category] => 0 [show_author] => 0 [link_author] => 0 [show_create_date] => 0 [show_modify_date] => 0 [show_publish_date] => 0 [show_item_navigation] => 0 [show_vote] => 0 [show_readmore] => 1 [show_readmore_title] => 0 [readmore_limit] => 100 [show_tags] => 0 [show_icons] => 0 [show_print_icon] => 0 [show_email_icon] => 0 [show_hits] => 0 [show_noauth] => 0 [urls_position] => 0 [show_publishing_options] => 1 [show_article_options] => 1 [save_history] => 1 [history_limit] => 10 [show_urls_images_frontend] => 0 [show_urls_images_backend] => 1 [targeta] => 0 [targetb] => 0 [targetc] => 0 [float_intro] => right [float_fulltext] => none [category_layout] => _:blog [show_category_heading_title_text] => 1 [show_category_title] => 0 [show_description] => 1 [show_description_image] => 0 [maxLevel] => 1 [show_empty_categories] => 0 [show_no_articles] => 1 [show_subcat_desc] => 1 [show_cat_num_articles] => 0 [show_cat_tags] => 1 [show_base_description] => 1 [maxLevelcat] => -1 [show_empty_categories_cat] => 0 [show_subcat_desc_cat] => 1 [show_cat_num_articles_cat] => 1 [num_leading_articles] => 0 [num_intro_articles] => 27 [num_columns] => 1 [num_links] => 4 [multi_column_order] => 0 [show_subcategory_content] => 0 [show_pagination_limit] => 1 [filter_field] => hide [show_headings] => 1 [list_show_date] => 0 [date_format] => [list_show_hits] => 1 [list_show_author] => 1 [orderby_pri] => order [orderby_sec] => rdate [order_date] => published [show_pagination] => 1 [show_pagination_results] => 1 [show_featured] => show [show_feed_link] => 1 [feed_summary] => 0 [feed_show_readmore] => 0 [show_page_heading] => 0 [layout_type] => blog [menu_text] => 1 [menu_show] => 0 [secure] => 0 [page_title] => Latest News [page_description] => Kielder Observatory Astronomical Society [page_rights] => [robots] => [access-view] => 1 ) [separator] => . ) [displayDate] => 2025-10-24 16:27:33 [slug] => 473:from-dark-skies-to-london-kielder-observatory-at-new-scientist-live-2025 [parent_slug] => [catslug] => 34:latest-news [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>Ever wondered what the Milky Way looks like away from city lights? Kielder Observatory brought the magic of the night sky to London with telescopes, VR experiences, stunning astrophotography, and interactive activities - inspiring thousands to look up, explore, and protect our stars. Discover how we engaged curious minds of all ages and shared the wonder of the cosmos.

)

AAA The Twilight Zone

From golden sunsets to the deep darkness of astronomical night, Astronomer Rosie reveals what really happens as our world turns from day to night, and why twilight is one of the most fascinating times for skywatchers

Read Time

7 minutes

From golden sunsets to the deep darkness of astronomical night, Astronomer Rosie reveals what really happens as our world turns from day to night, and why twilight is one of the most fascinating times for skywatchers

[fulltext] =>Introduction

Astronomers in the UK start getting very excited at the beginning of autumn because after being away for most of summer, night returns to us.

But what have we determined “night” to be? You might say it’s whenever the Sun sets, or whenever you are asleep to be night. But in astronomy, we have distinct and strict rules for what day, and night is.

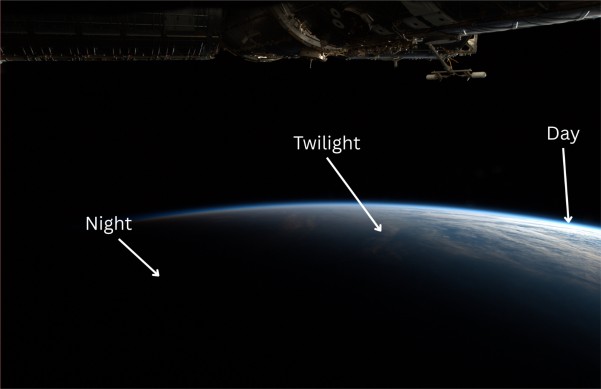

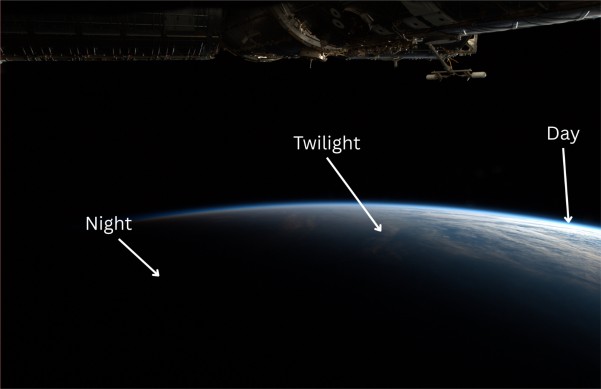

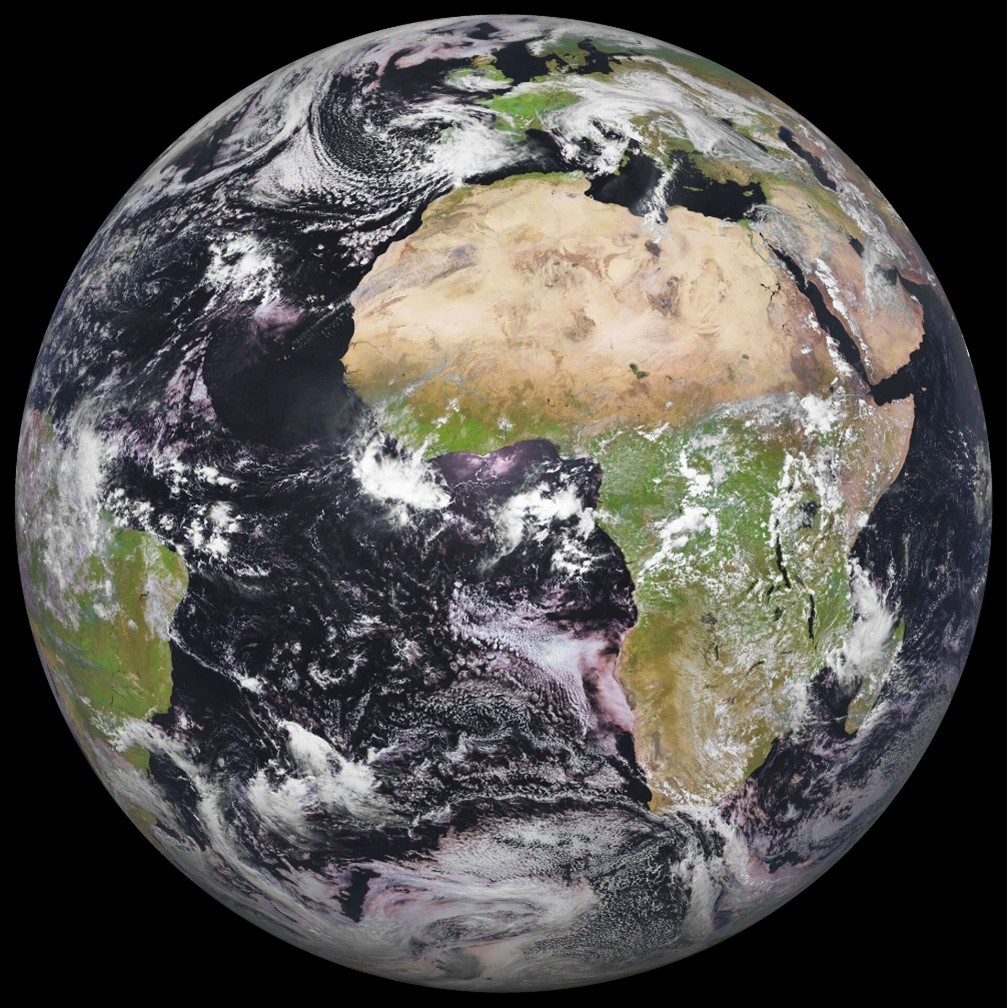

[Image: Perpetual Twilight at Earth's Terminator. Taken by astronaut Don Pettit, 01/20/12. Credit: NASA, International Space Station]

Day

Daytime, you can probably guess, is when the Sun is above the horizon. The sky is a brilliant blue, the birds are singing, and you can feel the rays on your face. There’s usually only one object that astronomers look at during the daytime, and that’s the Sun. Many observatories around the world will point their optical, radio or infrared telescopes towards the big ball of gas in the sky.

Then towards the end of the day, the Sun starts to get lower in the sky and head towards that horizon. This is the famous golden hour, the light is soft and red due to the Sun’s light having to penetrate through more atmosphere. It makes a great time for photography.

Then we get to sunset when the sun has just gone over the horizon. At this time we get very dramatic colours of pinks and oranges due to the Earth scattering the Sun’s light.

Twilight

When the Sun has set it doesn’t get dark immediately, there is still some ambient light around. What do we call this period? Twilight.

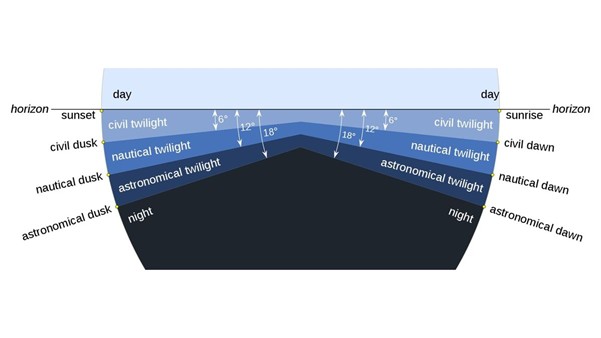

Astronomers have three distinct stages of twilight: civil twilight (just after sunset), nautical twilight, and astronomical twilight (the darkest of the three).

Let’s go over the three stages of twilight.

[Image credit: TWCARLSON/WIKIPEDIA/CC BY-SA 3.0]

Civil Twilight

This is the first stage that happens just after sunset. It's when the Sun is between 0 and 6 degrees below the horizon. The sky is still light enough to remain doing activities outside.

You might catch the brightest planets like Venus or Jupiter if they're well-placed in the sky. The Moon, if it's up, will be clearly visible, and sometimes you can spot bright stars like Sirius or Vega starting to peek through.

During these early stages of darkness is also a great time to see earthshine – sunlight that has bounced off the Earth and then back onto the Moon. Earth is actually much more reflective than the Moon (and a lot bigger), and so sometimes we can see that reflected light shining on our nearest neighbour! This only happens during new moon or when we have a thin crescent, because that’s when it’s a “full Earth” from the Moon’s perspective.

[Image. A thin crescent Moon exhibiting Earthshine in Kielder Forest. Credit: Dan Monk]

Nautical Twilight

Named so because this is where it looks like the sea and the sky merge together and it becomes difficult to find the horizon. This is when the Sun is between 6 and 12 degrees below the horizon. The sky will dim and you will be able to spot a few stars, which was important during the days of early navigation, as sailors could use the stars to find directions. We'll see constellations and asterisms begin to take shape - Orion, Cassiopeia, and the Summer Triangle become easier to identify. You’ll also start seeing more planets if they’re above the horizon, and satellites may be visible as they reflect sunlight before plunging into Earth’s shadow.

During nautical twilight in summer, you might also spot noctilucent clouds - ghostly wisps that drift high above the Earth. They’re not typical clouds, but layers of ice crystals floating in the mesosphere, around 85 km above sea level. Because of their extreme altitude, they can still catch sunlight even after the Sun has dipped well below the horizon - usually between 6 and 16 degrees, according to the World Meteorological Organization.

They appear as wispy, silvery streaks against the twilight sky. The further north you are, the better your chances of seeing them—especially if you’ve got a clear view to the northern horizon and the sky is still faintly lit by the Sun below.

[Image: Noctilucent clouds at Kielder Observatory. Credit: Jesse Beaman]

Astronomical Twilight

This is the darkest of the three, when the Sun is between 12 and 18 degrees below the horizon. There is still a remnant of light from the Sun, however faint stars and a few deep sky objects will start to appear (albeit dimly). This is where we can start to see the Milky Way appearing on a moonless evening.

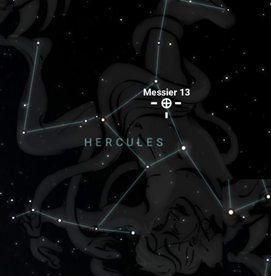

Galaxies like Andromeda (M31) and nebulae such as the Orion Nebula become visible to the naked eye or with binoculars, depending on sky conditions. Star clusters like the Pleiades or the Hercules Cluster (M13) also start to emerge. For astrophotographers, this is the point where long exposures begin to reveal rich detail in the night sky. Even though the night sky isn’t at its absolute darkest during astronomical twilight, some features—like city skylines, planets near the horizon, and noctilucent clouds—are actually best captured before full darkness sets in.

[Image: Milky Way during the summer months at Kielder Observatory. Credit: Dan Monk]

Night

Astronomers call “night” by another name - astronomical darkness. When astronomical darkness falls, astronomers yell “hoorary” and take out their telescopes again to view objects in the night sky. It’s when the Sun has gone so far below the horizon that there is no more ambient light ie. 18 degrees or more below the horizon. This is when the sky is darkest and clearest to see faint, far away things such as galaxies, nebulae, also our lovely Milky Way.

[Image: Astronomical darkness at Kielder Observatory. The darkest skies occur during this period when the Sun is more than 18 degrees below the horizon.]

When do we get Astronomical Darkness in the UK?

The time when astronomical darkness occurs depends on your location. During the early summer months in the UK, the Sun rests between 8 and 18 degrees below the horizon at night, meaning it never gets truly dark. Instead, all summer long we observe through twilight. In the northern parts of Scotland, they won’t even get astronomical twilight during the month of June.

[Image: Simmer Dim on Shetland during midsummer. Where sunset and sunrise merge together. Catherine Munroe]

However, by the time August comes around in England, we start to receive a few minutes of astronomical darkness in the early hours of the morning. By September that extends to 5 or 6 hours. This is why UK astronomers get very happy around autumn as there’ll be plenty of darkness to see very faint objects such as galaxies, nebula, and the pearly Milky Way.

[Image: A comparison between June and August. The darkest shade is astronomical darkness, the lighter shades are twilight. Left: 01:00 on the 21st of June. Right: 01:00 on the 21st of August. Credit: timeanddate.com]

We hope you enjoyed this article all about the twilight zone. See you at the observatory soon!

[checked_out] => 0 [checked_out_time] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [catid] => 34 [created] => 2025-10-10 15:53:17 [created_by] => 72927 [created_by_alias] => [modified] => 2025-10-10 15:56:45 [modified_by] => 72927 [modified_by_name] => Lindsey Brown [publish_up] => 2025-10-10 15:56:45 [publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [images] => {"image_intro":"images\/AAA\/AAAIMG1.jpg","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [urls] => {"urla":false,"urlatext":"","targeta":"","urlb":false,"urlbtext":"","targetb":"","urlc":false,"urlctext":"","targetc":""} [attribs] => {"show_title":"","link_titles":"","show_tags":"","show_intro":"","info_block_position":"","info_block_show_title":"","show_category":"","link_category":"","show_parent_category":"","link_parent_category":"","show_author":"","link_author":"","show_create_date":"","show_modify_date":"","show_publish_date":"","show_item_navigation":"","show_icons":"","show_print_icon":"","show_email_icon":"","show_vote":"","show_hits":"","show_noauth":"","urls_position":"","alternative_readmore":"","article_layout":"","show_publishing_options":"","show_article_options":"","show_urls_images_backend":"","show_urls_images_frontend":""} [metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"","rights":"","xreference":""} [metakey] => [metadesc] => [access] => 1 [hits] => 999 [xreference] => [featured] => 0 [language] => * [readmore] => 8945 [state] => 1 [category_title] => Latest News [category_route] => uncategorised/latest-news [category_access] => 1 [category_alias] => latest-news [author] => Lindsey Brown [author_email] => lindsey@kielderobservatory.org [parent_title] => ROOT [parent_id] => 1 [parent_route] => [parent_alias] => root [rating] => [rating_count] => [published] => 1 [parents_published] => 1 [alternative_readmore] => [layout] => [params] => Joomla\Registry\Registry Object ( [data:protected] => stdClass Object ( [article_layout] => _:default [show_title] => 1 [link_titles] => 0 [show_intro] => 1 [info_block_position] => 0 [info_block_show_title] => 0 [show_category] => 0 [link_category] => 0 [show_parent_category] => 0 [link_parent_category] => 0 [show_author] => 0 [link_author] => 0 [show_create_date] => 0 [show_modify_date] => 0 [show_publish_date] => 0 [show_item_navigation] => 0 [show_vote] => 0 [show_readmore] => 1 [show_readmore_title] => 0 [readmore_limit] => 100 [show_tags] => 0 [show_icons] => 0 [show_print_icon] => 0 [show_email_icon] => 0 [show_hits] => 0 [show_noauth] => 0 [urls_position] => 0 [show_publishing_options] => 1 [show_article_options] => 1 [save_history] => 1 [history_limit] => 10 [show_urls_images_frontend] => 0 [show_urls_images_backend] => 1 [targeta] => 0 [targetb] => 0 [targetc] => 0 [float_intro] => right [float_fulltext] => none [category_layout] => _:blog [show_category_heading_title_text] => 1 [show_category_title] => 0 [show_description] => 1 [show_description_image] => 0 [maxLevel] => 1 [show_empty_categories] => 0 [show_no_articles] => 1 [show_subcat_desc] => 1 [show_cat_num_articles] => 0 [show_cat_tags] => 1 [show_base_description] => 1 [maxLevelcat] => -1 [show_empty_categories_cat] => 0 [show_subcat_desc_cat] => 1 [show_cat_num_articles_cat] => 1 [num_leading_articles] => 0 [num_intro_articles] => 27 [num_columns] => 1 [num_links] => 4 [multi_column_order] => 0 [show_subcategory_content] => 0 [show_pagination_limit] => 1 [filter_field] => hide [show_headings] => 1 [list_show_date] => 0 [date_format] => [list_show_hits] => 1 [list_show_author] => 1 [orderby_pri] => order [orderby_sec] => rdate [order_date] => published [show_pagination] => 1 [show_pagination_results] => 1 [show_featured] => show [show_feed_link] => 1 [feed_summary] => 0 [feed_show_readmore] => 0 [show_page_heading] => 0 [layout_type] => blog [menu_text] => 1 [menu_show] => 0 [secure] => 0 [page_title] => Latest News [page_description] => Kielder Observatory Astronomical Society [page_rights] => [robots] => [access-view] => 1 ) [separator] => . ) [displayDate] => 2025-10-10 15:53:17 [slug] => 472:aaa-the-twilight-zone [parent_slug] => [catslug] => 34:latest-news [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

From golden sunsets to the deep darkness of astronomical night, Astronomer Rosie reveals what really happens as our world turns from day to night, and why twilight is one of the most fascinating times for skywatchers

)

World Space Week - The Future of Space Travel & Living in Space

This World Space Week, discover what it’s really like to live beyond Earth. From sleeping and eating aboard the International Space Station to the challenges of surviving on the Moon and Mars, humans are learning how to live and work in space. Explore how astronauts adapt to life in space, the experiments that help us survive off-world, and what the next steps in lunar and Martian exploration could mean for the future of humanity.

Read Time

7 minutes

This World Space Week, discover what it’s really like to live beyond Earth. From sleeping and eating aboard the International Space Station to the challenges of surviving on the Moon and Mars, humans are learning how to live and work in space. Explore how astronauts adapt to life in space, the experiments that help us survive off-world, and what the next steps in lunar and Martian exploration could mean for the future of humanity.

[fulltext] =>The Future of Space Travel: Where Curiosity Takes Us Next

For as long as we’ve looked up at the stars, we’ve imagined what it might be like to travel among them. At Kielder Observatory, that same curiosity drives everything we do - exploring, learning, and wondering about our place in the universe. And now, as technology takes bold new steps, the dream of venturing deeper into space is closer than ever before.

Living and Working in Space

Above our heads, about 250 miles up, the International Space Station (ISS) has become our home in orbit. A unique laboratory where astronauts from around the world live, sleep, eat, and work while circling Earth every 90 minutes. It might sound glamorous, but life in space is far from easy. Being in constant freefall, and floating around all the time, means simple tasks like brushing your teeth, eating a meal, or getting a good night’s sleep require practice and patience.

The ISS is more than a home; it’s a scientific laboratory where thousands of experiments are carried out in microgravity. These studies help us understand how the human body changes in space, how muscles weaken, bones lose density, and how our minds adapt to isolation and confined living. The lessons learned here are essential for our next big steps: living on the Moon and eventually Mars.

This image of the International Space Station (ISS) was photographed by one of the crewmembers of the STS-105 mission from the Shuttle Orbiter Discovery after separating from the ISS. Image: NASA

The Challenges of Living Beyond Earth

Surviving away from Earth is a huge challenge. The Moon has no breathable atmosphere and experiences extreme temperature swings, scorching hot in sunlight and freezing cold in darkness. Mars, still with some significant temperature swings, just not as extreme as the Moon, has a thin atmosphere made mostly of carbon dioxide, and dust storms that can last for months.

Astronauts will need habitats that can shield them from radiation, generate power, recycle air and water, and grow food in conditions unlike anything on Earth. Scientists are already testing 3D-printed lunar bases, space-grown plants, and robotic support systems that could one day make long-term living on other worlds possible.

Even something as simple as a meal will change. Future explorers might eat fresh vegetables grown under artificial light or rely on carefully designed nutrient packs. Sleep cycles will also be different, with long days and nights that can last weeks or months depending on where they are in the solar system.

Despite these difficulties, each challenge brings innovation. Learning how to live off-world helps us design new technologies that make life better here on Earth, from clean energy systems to medical advances and sustainable living practices.

Back to the Moon, and on to Mars

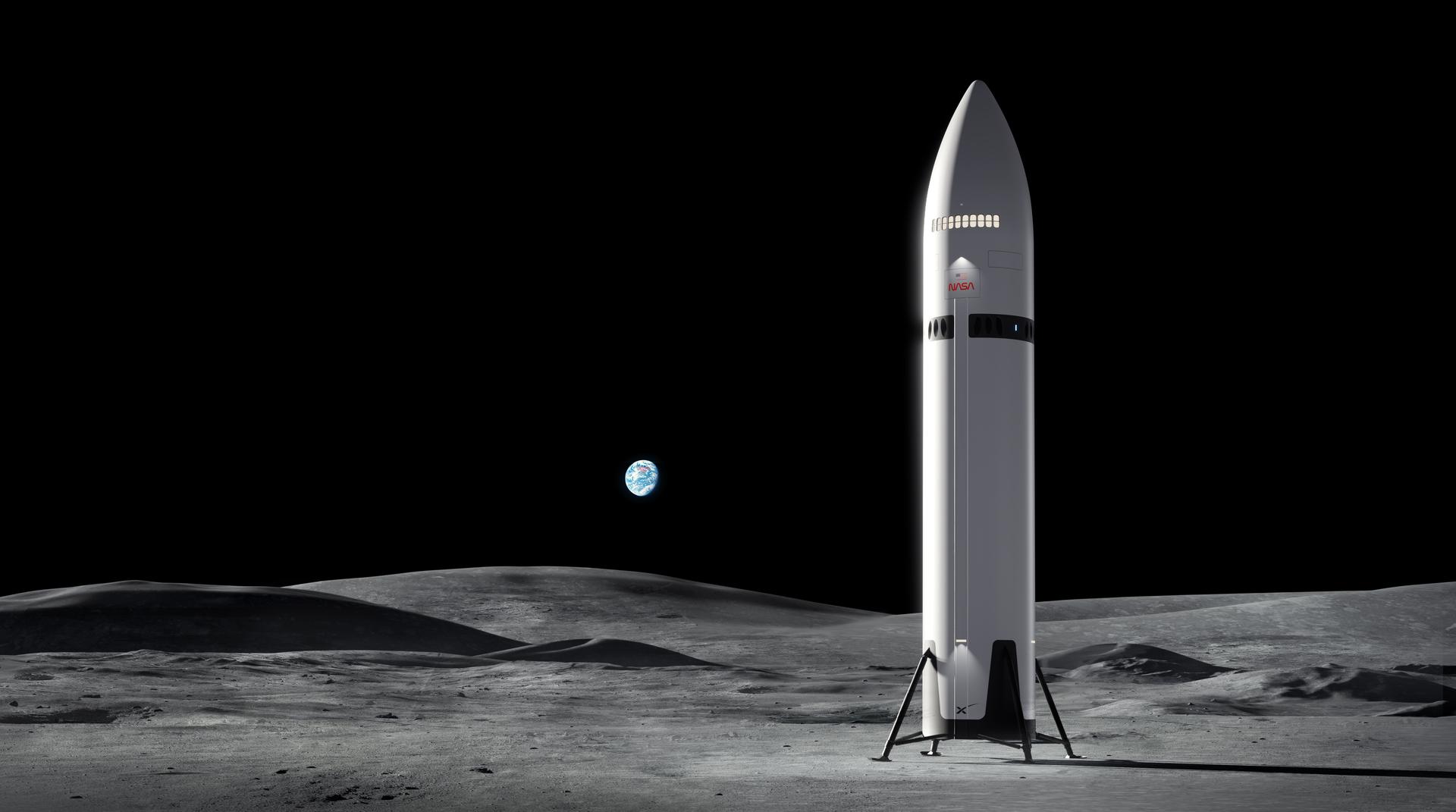

NASA’s Artemis programme is preparing to return humans to the Moon for the first time in over 50 years, not just to visit, but to stay. The next few years promise to be some of the most exciting in space exploration for a generation.

Artemis II, planned for launch soon, will carry astronauts beyond Earth’s orbit and around the Moon, marking the first time humans have left Earth orbit since 1972. The following mission, Artemis III, aims to return astronauts to the lunar surface for the first time in over half a century. While earlier plans highlighted the goal of landing the first woman and the first person of colour on the Moon, NASA has since updated its public language in line with recent U.S. government policy changes. Regardless of administration, the Artemis programme continues to represent a major step forward in human exploration, paving the way for a sustained presence on and around the Moon, and eventually, the journey to Mars.

These missions are laying the groundwork for a sustainable human presence on and around the Moon. Plans for the Lunar Gateway, a small space station that will orbit the Moon, will allow astronauts to live and work there for longer periods and serve as a launch point for future missions to Mars. Each step brings us closer to becoming a multi-planet species, one small step at a time.

These artist’s concepts show SpaceX’s Starship Human Landing System (HLS) on the Moon. Image: NASA

A Global Effort

Space exploration has become a truly international adventure. The European Space Agency (ESA) is developing its own lunar lander and working closely with NASA on Artemis. India recently made history with its Chandrayaan-3 lunar mission, and Japan, China, and the United Arab Emirates are all sending their own missions to the Moon and Mars. Each nation contributes its own expertise, showing that space exploration thrives when we share knowledge and ambition.

Launch vehicle lifting off from the Second Launch Pad (SLP) of SDSC-SHAR, Sriharikota. Image: Indian Space Research Organisation (GODL-India)

The New Space Race — Private and Public

It’s not just governments reaching for the stars. Companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin are revolutionising how we travel beyond Earth, developing reusable rockets that make spaceflight more sustainable and affordable. These partnerships between private industry and national space agencies are shaping a new era of exploration, one that could soon open the door to commercial flights, tourism, and research in orbit.

NASA astronaut Matthew Dominick, commander of NASA’s SpaceX Crew-8 mission, is suited up to participate in a Crew Equipment Interface Test (CEIT) at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida on Friday, Jan. 12, 2024. Image: NASA

Why It Matters

Exploring space is about more than discovery, it’s about progress. The technologies developed for space travel often lead to breakthroughs on Earth: medical devices, water purification systems, solar energy, and even the camera sensors in our smartphones all trace their origins to space research. By pushing our boundaries, we push innovation forward.

It’s also a powerful investment in the future. Countries that fund space programmes don’t just explore the cosmos, they fuel their own economies. These projects create hundreds of thousands of jobs and spark industries in engineering, computing, and manufacturing. Studies from 1971 and again in 2016 found that for every dollar the U.S. government invested in space exploration, the return was between $7 and $14, depending on the mission. That’s a remarkable return, and a reminder that when we reach for the stars, we lift up life here on Earth too.

Keeping Wonder Alive

Here on Earth, our journeys into space remind us to look up and stay curious. Every rocket launch, every new discovery, and every shimmering star above Kielder’s dark skies tells part of a much bigger story - one of human imagination, collaboration, and courage.

So next time you visit Kielder Observatory and gaze at the Milky Way stretching above Northumberland, remember: the future of space travel isn’t just about reaching other worlds, it’s about continuing the greatest journey of all, fuelled by curiosity and the human spirit.

The Milky Way stretching across the dark skies in Kielder. Image: Kielder Observatory