AAA- What is a constellation?

Welcome to our “Ask An Astronomer” series where we answer the questions we regularly receive from members of the public during events and online. In this article our astronomer Ellie will be answering the question “What is a constellation?”.

So, what is a constellation?

Quick Answer...

A constellation is an apparent pattern of stars seen in the night sky. Different cultures have been dividing the sky up for as long as we have written records, starting in ancient Mesopotamia. As a result, there is a rich diversity in cultural views of the night sky, from lunar to solar systems based around the ecliptic as favoured in Europe and Asia, to systems based entirely around the Milky Way with constellations made from cosmic dust as in Andean astronomy. Since 1930 the International Astronomy Union has recognised 88 constellations which divide the sky. As well as formal constellations there are informal asterisms such as the Plough and the summer and winter triangles. These are most often used by amateur astronomers to navigate around the sky and to indicate the seasons.

Long Answer...

It’s easy to feel small when you stargaze, simply imagine the thousands of stars in your sky in their proper homes trillions of miles away, distant neighbours sending you messages in the form of light, messages that take sometimes millennia to arrive. It’s easy to become overwhelmed too, we’ve all been there. When faced with something so immense, I think it is the most human thing in the world to make patterns to try and break it all up- this is what constellations do.

A constellation is an apparent pattern of stars in the sky. These patterns are created by joining together the stars like a cosmic dot-to-dot until they resemble some such thing as a dog, or a bear, or a tragic heroine chained to a rock and left as a sacrifice to some sea monster, or some hair. Some resemble themselves better than others.

The practise of creating constellations is an old one with the earliest star lists coming from Babylon around the 12th Century BC. Some constellations still in use today can be traced back to these star lists, for example Taurus and Gemini. Initially, the purpose of these constellations may have been to act as a calendar, there exists examples of Babylonian planispheres showing the sky divided into 12 equal portions, each associated with a constellation. In time we know the sky acquired a more divine association as planets were named for important gods and goddesses, and stories began to appear to explain how the constellations came to be in the sky. The earliest example we have of star lore in this sense is the story of the Great Bull of the Heavens from the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Cuneiform planisphere and recreation

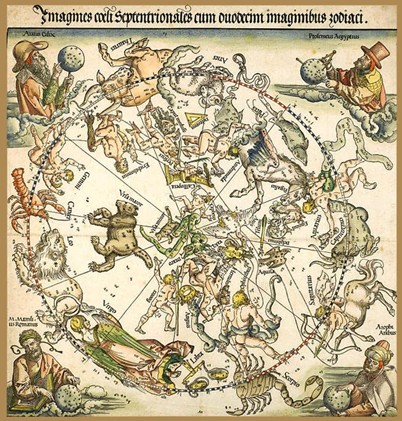

Babylonian astronomy spread to Egypt and from there it spread to Greece. In the 2nd century AD Claudius Ptolemy, an astronomer and mathematician from Alexandria, wrote the Almagest, a mathematical treatise about the motions of stars and planets, and a summary of Greek astronomical knowledge. In this he listed 48 constellations and defined their figures for generations to come.

Ptolemy’s 48 constellations from the Almagest

Across the world, different constellation systems have been developed though. In China, for example, by the 13th century their view of the sky had developed to include 283 constellations. Astronomers here divided the sky into 4 sections called Azure Dragon, Black Tortoise, White Tiger, and Vermilion Bird. Each of these sections was further divided into 7 mansions along the ecliptic to give 28 mansions in total, these correspond to the motion of the Moon through the lunar month. The sky was also divided into the Purple Forbidden enclosure, the Heavenly Market enclosure, and the Supreme Palace enclosure.

Whilst European and Asian systems were generally centred around the ecliptic, the plane of the solar system and therefore the path the sun, moon, and planets will take through the sky, when the Spanish arrived in America, they were surprised to find the Inca with a view of the sky that focussed on the Milky Way instead. Inca astronomers divided the sky into 4 quadrants based on the rotation of the Milky Way overhead over a 24-hour period. In this sky they had 2 kinds of constellation, one being the familiar dot-to-dot of stars, but the other being dark constellations made using the dark dusty regions in the plane of the Milky Way.

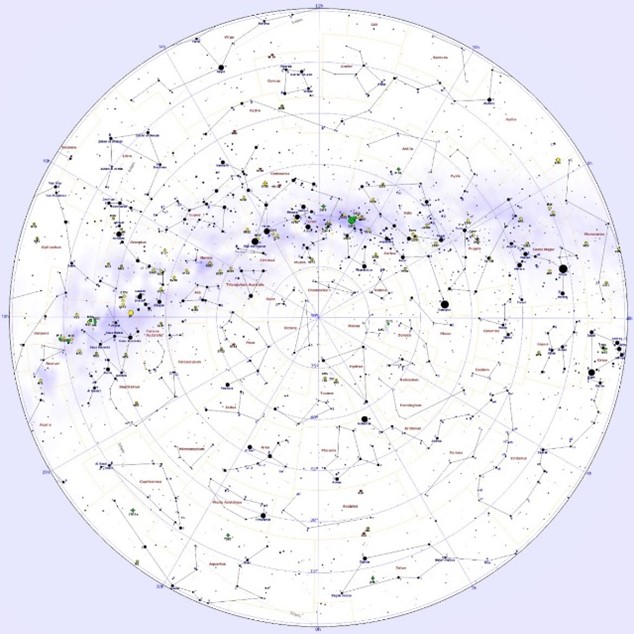

As the world became more interconnected, and astronomers more taken to collaborate across continents, these different systems came into conflict. To further complicate things, it became rather trendy amongst European Astronomers to “find” new constellations to dedicate them to some important patron. By the 19th Century, the sky was getting just a bit crowded, and there were some disagreements over names and exact boundaries. To try and resolve some of these issues, the International Astronomical Union stepped in. In the first IAU general assembly, held in Rome in 1922, they set about to determining an internationally agreed upon set of constellations. The Commission on Notations and Units agreed on a list of 88 constellations across the whole sky, and they set about agreeing on the boundaries. By 1928 the boundaries as we know them today were approved, and in 1930 they were published to the wider world.

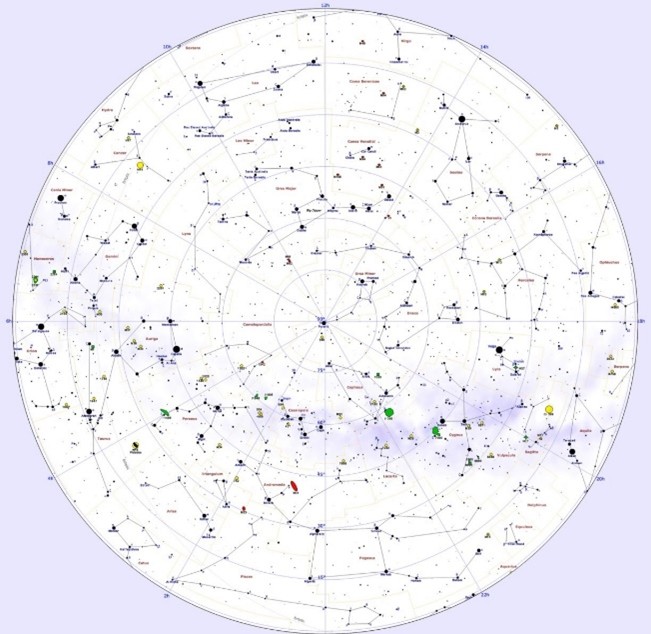

Northern and Southern celestial hemispheres with constellations. Image: Roberto Mura

The 88 constellations in the IAU list do have a significant bias towards the “Greco-Roman” tradition, you won’t find any Chinese or Inca constellations on the list for example, but I think that this can broadly be explained by the state of the IAU in 1922. As the first general assembly ended there were 19 member nations: Belgium, Canada, France, Great Britain, Greece, Japan, USA, Italy, Mexico, Australia, Brazil, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, South Africa, and Spain. Within academic circles in these countries, it was likely that Greco-Roman constellations were already the established norm, the activity of formalising this was mostly about removing some of the more modern constellations.

With the existence of “formal” constellations, that does now open the sky up to informal constellations a.k.a. asterisms. Anyone can make an asterism; it is simply any pattern of any stars not recognised by the IAU. Some asterisms really take off too- look at the Plough/the Big Dipper! Consisting of just the back portion of the IAU accredited Ursa Major, the Plough is a handy asterism for finding the North Star. You simply start on the curved handle and follow the seven stars around, using the last two to create a line that you follow up across the sky until you hit Polaris, the North Star. Astronomers are also fond of using the summer and winter triangles as indicators of the observing season, harkening back to the ancient tradition of using the sky as a calendar.

So what is a constellation? Whatever you want it to be. The IAU might disagree with you, but as long as you call it an asterism, you’re covered.