What's Up? February 2026

February may be short, but the winter nights are still long and packed with sky-watching treats. From bright winter star patterns and the beautiful Beehive Cluster to dazzling planets, and even the chance of a comet! There’s plenty for naked-eye observers and telescope users to enjoy this month.

The month may be short, but the nights are still long so it’s a great time to get out and look up. This month we have planets, galaxies, and potentially a comet for telescope users.

Constellations

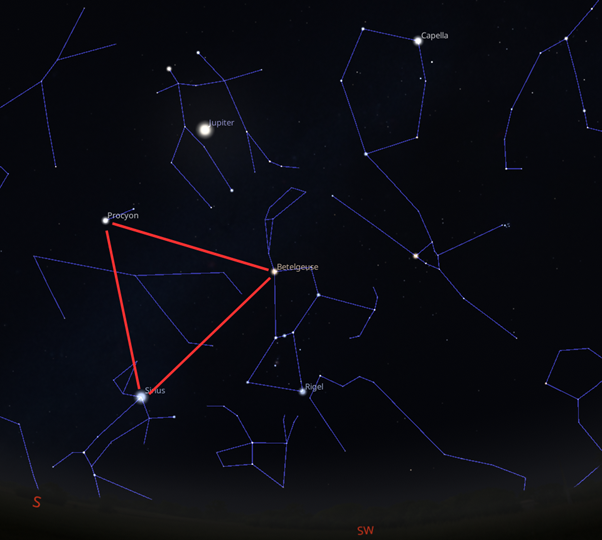

It’s still winter, so looking up we have the usual suspects, like Orion, dominating the night sky providing several brilliantly bright stars. In the past we have talked about the Summer Triangle, an asterism created from Vega (in Lyra), Deneb (in Cygnus), and Altair (in Aquila) which sits high in the sky throughout the Summer months. To compliment this, there is also a Winter Triangle consisting of Sirius (Canis Major), Procyon (Canis Minor) and Betelgeuse (Orion), three of the brightest stars in the winter night sky.

The night sky as seen on the 14th February at 2200 from Kielder Observatory, simulated on Stellarium. The asterism known as the Winter Triangle is marked out.Credit: Stellarium

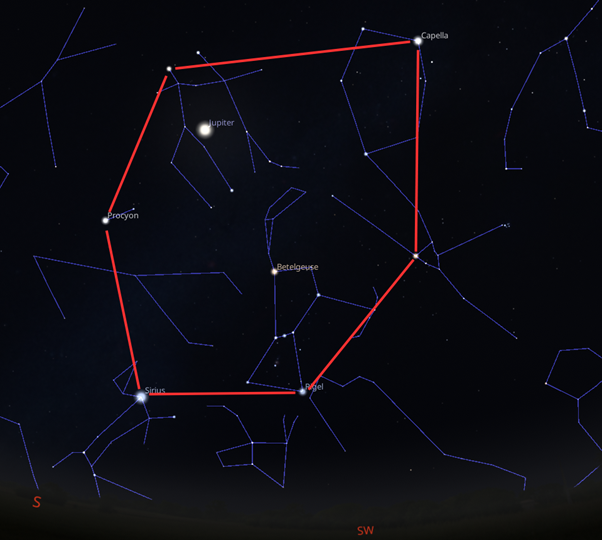

However, if 3 stars isn’t enough for you, there is also the Winter Hexagon of Sirius (Canis Major), Procyon (Canis Minor), Pollux (Gemini), Capella (Auriga), Aldebaran (Taurus), and Rigel (Orion).

The night sky as seen on the 14th February at 2200 from Kielder Observatory, simulated on Stellarium. The asterism known as the Winter Hexagon is marked out. Credit: Stellarium

Asterisms like this can be a good way to boost your night sky knowledge, if you are learning how to spot the constellations they give you bright target stars to look out for. February is a great month to try and spot these stars because all of them are above the horizon for the full duration of the night. They are all also bright enough to be seen in light pollution, whether that’s natural light pollution from the Moon or artificial light pollution from street lights and the such. So really – there’s no excuse.

Object of the Month – The Beehive (M44)

I consider Cancer to be one of the more difficult constellations to spot in the sky. Although it inhabits a high position through dark winter and spring months, the stars that make up the crab are pretty faint and difficult to pick out. The brightest star, Tarf, has a visual magnitude of +3.5 which makes it the 297th brightest star in the sky. Because of this, it is often easier to find Cancer by not looking for it’s stars, but rather it’s brightest cluster – The Beehive!

The Beehive cluster, also known as M44, is a bright open cluster that has been known about since ancient times. Claudius Ptolemy described it as a “nebulous mass in the breast of Cancer” and that is a pretty apt description. Historically the description of “nebulous” was applied much more widely than today to describe anything that appeared fuzzy, foggy, or cloud-like, and so in older texts you will find it applied to clusters, nebulas, and galaxies alike. It is, as the observation by Ptolemy suggests, visible to the naked eye but it is fairly faint and so you will see it best out of the corner of your eye, an old trick in astronomy known as “averted vision”.

To find it, I would suggest locating the brighter constellations of Leo and Gemini, and then letting your eye wander between the two until something catches it. Or, if you want something more precise, draw a line between Castor and Regulus and the Beehive should sit roughly below the mid-point.

Leo, Cancer, and Gemini in a row. The Beehive Cluster is marked in Cancer by a ring of yellow dots and it sat mid-way between Leo and Gemini. Credit: Stellarium

The cluster is thought to be made up of 1000 stars believed to be all around 600 million years old and it is located around 600 light years away. It was one of the first objects studied by Galileo Galilei with his telescope in 1609 and looking at the cluster he was able to resolve 40 stars.

M44, the Beehive Cluster. Credit: Sauro Gaudenzi 7 Data Telescope Live

Planets

This is the last chance you have to see Saturn for a few months as it approaches the Sun, but as it emerges from the other side in April it will only be visible for a short time in the pre-dawn sky. It will them get better as it moves further from the glare of our closest star, but you’ll be waiting months for that! If you’ve missed Saturn so far this winter, look for it towards the West as it gets dark and it will be the brightest “star” visible fairly low to the horizon.

Jupiter will continue to stun as it sits high up in the sky in the constellation of Gemini, turning the twins into triplets. It will be visible all night from sunset to sunrise.

Towards the end of the month on the 19th Mercury will reach it’s greatest east elongation from the Sun, which means that it will be visible in the sky shortly after sunset. On the 20th it will be at its highest altitude in the evening sky. Being the closest planet to the Sun, Mercury always follows or leads close to the Sun in our sky making it one of the trickier planets to observe, this could be your chance! In fact, for those who are able to find a low enough western horizon there is a chance to see a mini-planetary parade with Mercury, Venus, and Saturn all clustered together in the west shortly after sunset and Jupiter in the south east.

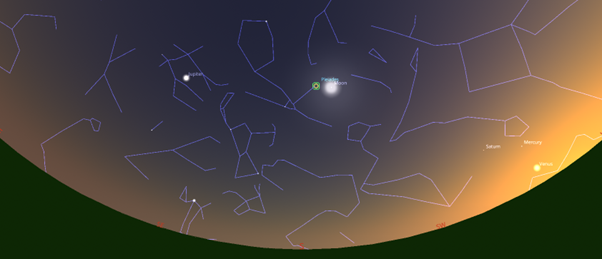

The sky from Kielder Observatory on the 23rd February at 1805 looking south, simulated on Stellarium. Credit: Stellarium

The Moon

Full Moon: 1st February

Last Quarter: 9th February

New Moon: 17th February

First Quarter: 24th February

Antarctic Annular Eclipse

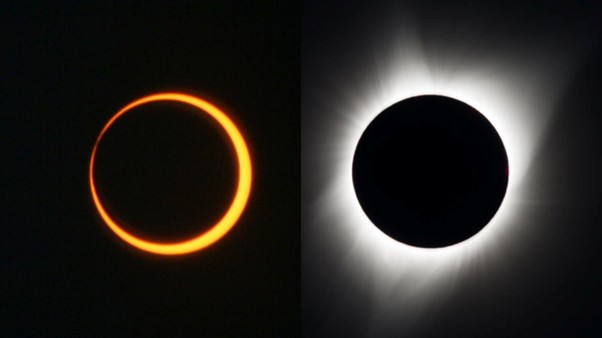

An annular solar eclipse (left) vs a total solar eclipse (right). Credit: NASA/Bill Dunford, left, and NASA/Aubrey Gemignani, right

I think it’s fairly unlikely that anyone reading this finds themselves planning to be in Antarctica this February, but in the off chance that someone’s got plans that way I feel obliged to inform them of the annular solar eclipse which will be visible on the 17th February around midday.

A solar eclipse occurs as the Moon passes between the Earth and the Sun, obscuring part or all of the Sun in the process. An annular solar eclipse, sometimes called a “ring of fire” eclipse, occurs when the Moon passes completely between the Earth and the Sun while the Moon is at apogee (the most distant point in its elliptical orbit around the Earth). When this happens, the Moon appears to be slightly smaller than the Sun and so as it blocks the centre, a small ring of light can still be seen around the edge.