AAA The Twilight Zone

From golden sunsets to the deep darkness of astronomical night, Astronomer Rosie reveals what really happens as our world turns from day to night, and why twilight is one of the most fascinating times for skywatchers

Introduction

Astronomers in the UK start getting very excited at the beginning of autumn because after being away for most of summer, night returns to us.

But what have we determined “night” to be? You might say it’s whenever the Sun sets, or whenever you are asleep to be night. But in astronomy, we have distinct and strict rules for what day, and night is.

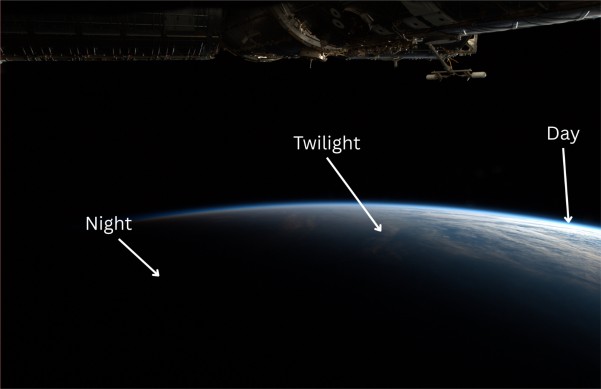

[Image: Perpetual Twilight at Earth's Terminator. Taken by astronaut Don Pettit, 01/20/12. Credit: NASA, International Space Station]

Day

Daytime, you can probably guess, is when the Sun is above the horizon. The sky is a brilliant blue, the birds are singing, and you can feel the rays on your face. There’s usually only one object that astronomers look at during the daytime, and that’s the Sun. Many observatories around the world will point their optical, radio or infrared telescopes towards the big ball of gas in the sky.

Then towards the end of the day, the Sun starts to get lower in the sky and head towards that horizon. This is the famous golden hour, the light is soft and red due to the Sun’s light having to penetrate through more atmosphere. It makes a great time for photography.

Then we get to sunset when the sun has just gone over the horizon. At this time we get very dramatic colours of pinks and oranges due to the Earth scattering the Sun’s light.

Twilight

When the Sun has set it doesn’t get dark immediately, there is still some ambient light around. What do we call this period? Twilight.

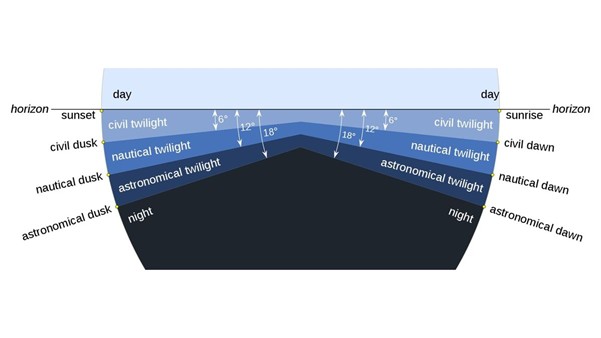

Astronomers have three distinct stages of twilight: civil twilight (just after sunset), nautical twilight, and astronomical twilight (the darkest of the three).

Let’s go over the three stages of twilight.

[Image credit: TWCARLSON/WIKIPEDIA/CC BY-SA 3.0]

Civil Twilight

This is the first stage that happens just after sunset. It's when the Sun is between 0 and 6 degrees below the horizon. The sky is still light enough to remain doing activities outside.

You might catch the brightest planets like Venus or Jupiter if they're well-placed in the sky. The Moon, if it's up, will be clearly visible, and sometimes you can spot bright stars like Sirius or Vega starting to peek through.

During these early stages of darkness is also a great time to see earthshine – sunlight that has bounced off the Earth and then back onto the Moon. Earth is actually much more reflective than the Moon (and a lot bigger), and so sometimes we can see that reflected light shining on our nearest neighbour! This only happens during new moon or when we have a thin crescent, because that’s when it’s a “full Earth” from the Moon’s perspective.

[Image. A thin crescent Moon exhibiting Earthshine in Kielder Forest. Credit: Dan Monk]

Nautical Twilight

Named so because this is where it looks like the sea and the sky merge together and it becomes difficult to find the horizon. This is when the Sun is between 6 and 12 degrees below the horizon. The sky will dim and you will be able to spot a few stars, which was important during the days of early navigation, as sailors could use the stars to find directions. We'll see constellations and asterisms begin to take shape - Orion, Cassiopeia, and the Summer Triangle become easier to identify. You’ll also start seeing more planets if they’re above the horizon, and satellites may be visible as they reflect sunlight before plunging into Earth’s shadow.

During nautical twilight in summer, you might also spot noctilucent clouds - ghostly wisps that drift high above the Earth. They’re not typical clouds, but layers of ice crystals floating in the mesosphere, around 85 km above sea level. Because of their extreme altitude, they can still catch sunlight even after the Sun has dipped well below the horizon - usually between 6 and 16 degrees, according to the World Meteorological Organization.

They appear as wispy, silvery streaks against the twilight sky. The further north you are, the better your chances of seeing them—especially if you’ve got a clear view to the northern horizon and the sky is still faintly lit by the Sun below.

[Image: Noctilucent clouds at Kielder Observatory. Credit: Jesse Beaman]

Astronomical Twilight

This is the darkest of the three, when the Sun is between 12 and 18 degrees below the horizon. There is still a remnant of light from the Sun, however faint stars and a few deep sky objects will start to appear (albeit dimly). This is where we can start to see the Milky Way appearing on a moonless evening.

Galaxies like Andromeda (M31) and nebulae such as the Orion Nebula become visible to the naked eye or with binoculars, depending on sky conditions. Star clusters like the Pleiades or the Hercules Cluster (M13) also start to emerge. For astrophotographers, this is the point where long exposures begin to reveal rich detail in the night sky. Even though the night sky isn’t at its absolute darkest during astronomical twilight, some features—like city skylines, planets near the horizon, and noctilucent clouds—are actually best captured before full darkness sets in.

[Image: Milky Way during the summer months at Kielder Observatory. Credit: Dan Monk]

Night

Astronomers call “night” by another name - astronomical darkness. When astronomical darkness falls, astronomers yell “hoorary” and take out their telescopes again to view objects in the night sky. It’s when the Sun has gone so far below the horizon that there is no more ambient light ie. 18 degrees or more below the horizon. This is when the sky is darkest and clearest to see faint, far away things such as galaxies, nebulae, also our lovely Milky Way.

[Image: Astronomical darkness at Kielder Observatory. The darkest skies occur during this period when the Sun is more than 18 degrees below the horizon.]

When do we get Astronomical Darkness in the UK?

The time when astronomical darkness occurs depends on your location. During the early summer months in the UK, the Sun rests between 8 and 18 degrees below the horizon at night, meaning it never gets truly dark. Instead, all summer long we observe through twilight. In the northern parts of Scotland, they won’t even get astronomical twilight during the month of June.

[Image: Simmer Dim on Shetland during midsummer. Where sunset and sunrise merge together. Catherine Munroe]

However, by the time August comes around in England, we start to receive a few minutes of astronomical darkness in the early hours of the morning. By September that extends to 5 or 6 hours. This is why UK astronomers get very happy around autumn as there’ll be plenty of darkness to see very faint objects such as galaxies, nebula, and the pearly Milky Way.

[Image: A comparison between June and August. The darkest shade is astronomical darkness, the lighter shades are twilight. Left: 01:00 on the 21st of June. Right: 01:00 on the 21st of August. Credit: timeanddate.com]

We hope you enjoyed this article all about the twilight zone. See you at the observatory soon!